“Solving for X”: Seeking the Sacredness of Belonging in Crisosto Apache’s Ghostword

Crisosto Apache is the author of two volumes of poetry, GENESIS published by Lost Alphabet and Ghostword published by Gnashing Teeth Publication. An MFA graduate from Institute of American Indian Arts, they are Mescalero Apache, Chiricahua Apache, and Diné (Navajo) of the 'Áshįįhí (Salt Clan) born for the Kinyaa'áanii (Towering House Clan) and currently an Assistant Professor of English at the Rocky Mountain College of Art + Design. Their poems have been published in journals like Poetry magazine, The Rumpus, and anthologized in When the Light of the World was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through (WW Norton), edited by Joy Harjo.

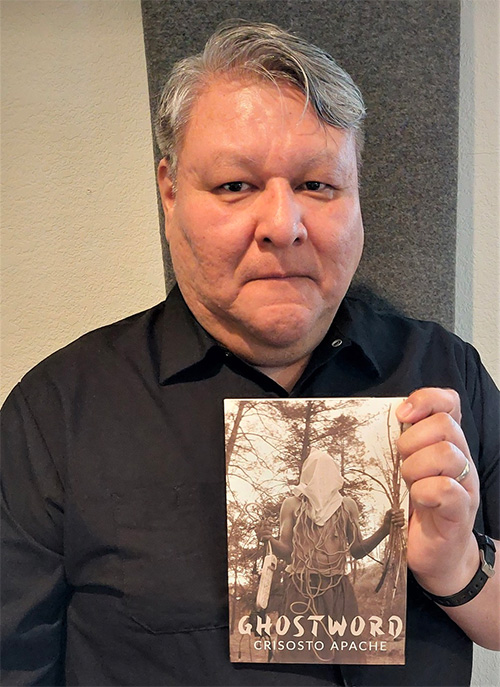

KW: I thought I would ask you to start out doing something a little bit different for this interview. I read in your biography that started out studying painting in college and then switched to poetry. Obviously, you are a very visual, image-oriented artist/poet. The cover of Ghostword, your second book of poetry, is so jaw-dropping, especially when all the disparate details in that photo come into view. Can you introduce us to your powerful book by talking about this image you created for its cover? What does it say about the poems we find in the book?

CA: Words by poets are highly misunderstood by most people, just as are the perspectives and processes of many artists, which is why their work is often discussed. Words have become integral to my work as an artist first, second, a writer, and finally, an individual. Understanding the perspective of an artist is a great mystery. The way I view objects or my surroundings is important in the way I observe the connection between myself and the objects. The idea of “space” and “place” are ideas I connect to a sense of belonging. Belonging is a sacred way of trying to exist and remember that existence through memory. We are all seeking to belong. Ghostword is an exploration of “place” and “space” through my memory. When I write a poem there is a huge connection to imagery because providing a visual allows the audience to explore that moment through the presence of the poem and the emotion the poem represents. Images work in the same way.

The cover is a photograph titled, “Unusual Spector” (2007), that I instinctively took spare-the-moment while on a visit back home on my reservation. The photo originally was in color but I changed the hue to a Sepia tone to give a vintage feel, which adds to the hauntingly jarring depiction. The concept for the image is loosely based on one of the mountain spirit deities in the Mescalero Apache ceremonial tradition called Łíbayí (often referred to as “clowns”). The concept for Ghostword (which is the title of the book and poem numbered 26) has had a long journey and when I took the photo the concept for the book became solidified. The contrast between two moments of time is what I had in mind and how blindly mankind occupies and acknowledges these spaces. The images then represent a conversation with the past which is where Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s writing takes hold. Because of the nature of Akutagawa’s death by suicide, his writing was still speaking through the carbon copy of his last manuscript, A Fool’s Life, which I carried for many years until I was able to find a copy. Much of his work had gone out of print. While carrying that carbon copy, it felt like Akutagawa was with me, like a spirit or ghost, where the title of the book comes from.

KW: The genesis of your book is pretty mind-blowing, too. Just to fill in a few details for our readers: Ryūnosuke Akutagawa was a Japanese writer born in 1892 who took his life 35 years later by an overdose of barbital. It took him three hours to die and in that time he wrote 51, what you call, vignettes. His work continued to be influential and you, as a student, got a carbon copy of that last book, A Fool’s Life. And that is what inspired you to write Ghostword. Besides giving us a look at the process you went through in writing your book, can you share with us what you see are the challenges and pluses of having a kind of reference book to model and to inspire your own writing? How did working with A Fool’s Life change your writing or did it? How do you see the passages you use from A Fool’s Life as quotes and epigraphs for your poems change and transform them?

CA: The beginning development of the book began with the three-hour time frame of Akutagawa’s death. Those three hours are what challenged me to write something, like a response. If given three hours to write an epilogue, if you will, what would I write back in 2010? Of course, working within that time frame was a complete failure, after two attempts. What came out of that challenge was the skeletal beginnings in two parts, and the third was a connection to Akutagaw’s other short stories. How to structure the book was difficult because I was posed with the decision to orchestrate the book chronologically or keep the book to the two sections. Choosing the order of the two sections best represented the process of how the book had come together, so I honored that process. At a later date, I added the third section as a reflective section of the process and to Akutagawa’s prevalent short stories.

KW: In one of your interviews I read online in The Big Smoke, you talk about not belonging and say “in terms of my own personality and who I was as a Native American, as a person, as a person who comes from a culture that is being eradicated.” I think one of the big challenges of writing a book of poetry is discovering its arc, that transformative movement, whatever that might be. The first poem of your book ends with the line: “my own half century’s end is still undetermined” and the concluding line of your last poem is:

“[*]

I am still solving for x.”

Take us through the journey of your book. I think there is some kind of transformation here, even as you are still searching, given the beautiful images in that last section’s poems like in ”Whitetail” when you are walking toward the empty house of your mother or in “Sleep,” a poem for your father with its image of “elegant cupping plumes of wet deer weed.” What did you finally learn about yourself in writing this book?

CA: The recognition of my existence has always remained a question at the back of my mind. Why I am so different from my family and siblings? Being the only family member with significant accomplishments has always placed me at odds with my immediate and extended family, as well as my tribal identity. The poem titled, “1. The Pages” (– after 1. The Ages, R.A.), in the sixth stanza, last line, there is the word “ik ł’dá”, which refers to “the beginning” of time, immemorially. An existence that lives within me but only survived about fifty of those years in that immemorial existence. Because I have experience adversity in my life, many of which I talk about in the book, I cannot or have not reconciled many of those experiences, hence the seeking to belong. This is the opposite of Akutagaw’s attempt to exist which was focused on the sense of “erasure.” Through all the adversity, I am always trying to see solace and peace of “self,” “still solving for x.” “Solving for x,” is a reference from my first book GENESIS (Lost Alphabet), where I experiment with the concept of “x” and “intersections.” The last poem of Ghostword mimics the layout of my first book, which was sectioned into ten parts, representing the gestation of human development from conception to the moment of birth (the unknowing). In some way, Ghostword attests to the same journey, but from an autobiographical perspective rather than an experimental format. Writing about real accounts was and is still difficult. The poems in this collection are real accounts of my own experience and stories my mother told me. The emotional energy contained in each poem is a testament not only to my struggle as an indigenous gay person but to the historical transmission of trauma we could not understand or escape. Trying to get my family to understand the disparity that surrounds the trauma passed down through generations is still difficult but deserves a space and place of belonging inside this book and on these pages. Many of the poems are emotionally difficult to read because of the backstories. Maybe this is an attempt to absolve the “self” and release all of the “ghosts”.

KW: Two poetry collections out now. What’s next?

CA: Having a writing project lined up is a good thing and keeps my mind occupied and cultivated. Many of the poems in this collection have already been published in many literary journals and artist projects. Future perspective projects give me something to look forward to. I am finishing up my third manuscript, called is(ness). The concept behind this manuscript is poems that represent “meaning-fulness” of the poem in a state of presence or what I am calling the “momentary poem”. What the poem is “about” in a state of existence as it “exists” without retribution or containment. The work in is(ness) at times feels complicated because of how poetry or art is defined by “others.” What I choose to exemplify in this manuscript is a concept where the poem is a poem that is about what the poem is in a state of “meaning-fulness.” My goal for this manuscript it to have in a publisher's hands by the end of the year, if not sooner, (fingers crossed).

“Kúghą/Home” from Poetry Magazine