Interrogating the Visual World with Katherine Indermaur: The I|I in the Looking Glass

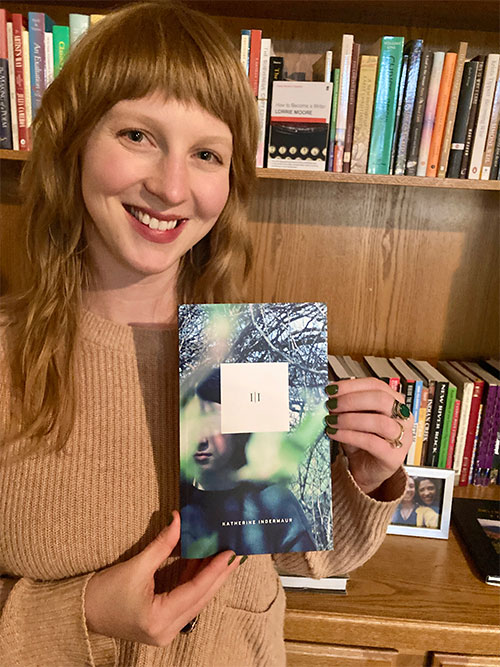

Katherine Indermaur’s first full poetry collection, I½I, won the Deborah Tall Lyric Essay Book Prize and the Colorado Book Award in Poetry. She is also the author of two chapbooks, Facing the Mirror: An Essay (Coast|noCoast, 2020) and Pulse (Ghost City Press, 2018). An editor for Sugar House Review, she has published work in literary journals such as ecotone, Frontier Poetry, and Seneca Review.

Katherine Indermaur’s first full poetry collection, I½I, won the Deborah Tall Lyric Essay Book Prize and the Colorado Book Award in Poetry. She is also the author of two chapbooks, Facing the Mirror: An Essay (Coast|noCoast, 2020) and Pulse (Ghost City Press, 2018). An editor for Sugar House Review, she has published work in literary journals such as ecotone, Frontier Poetry, and Seneca Review.

KW: Congratulations, Katherine, for winning the 2022 Deborah Tall Lyric Essay Book Prize and the 2023 Colorado Book Award in Poetry for the same book, I½I! Your double win in two genres, I think, perfectly points out the deep “genre-mingling” between lyric essays/ poems. The Seneca Review, which was one of the first journals to “coin” the term the lyric essay and runs the Deborah Tall contest, has a wonderful description of the lyric essay on their website. Can you talk to us about writing a book that is both a vestige of the lyric essay and of the poem? In my mind, I keep seeing this image of you½you skiing along in the trough of two powerful crests that are taking you on a most difficult journey where the threat of drowning is always omnipresent. In that Seneca Review description of the lyric essay is a wonderful quote by Paul Celan that perfectly matches what I felt in your book, lyric essays or poetry: The poem is lonely. It is lonely and en route. Its author stays with it.

KI: Thank you, Kathy, and thanks for spending time with me and my work. I love the lyric essay for how it refuses easy categorization—reduction of any kind. It refuses, as Deborah Tall and John D’Agata wrote on that same wonderful webpage, “the myth of objectivity.” I first started writing I|I with what I considered to be prose poems. As those began accruing and then cohering around their own logic on the subject of mirrors, I realized something bigger, something truly hybrid was at work. I approached writing I|I very much as a poet and with a poet’s training, and will admittedly bristle a bit if someone wants me to talk about the book as pure nonfiction. Along the way, I would occasionally submit excerpts of this book for publication in literary magazines under the poetry genre only to have editors ask me if they could publish it as nonfiction. Those editors helped me reconsider my own genre allegiances. Some of my favorite lyric essayists came to the form from poetry, too. I think my poetry background allows me to consider form as a world of possibility rather than only a set of conventions, and feels really well suited to this book’s interrogation of the visual world. The book also, as you mention, goes on a difficult inner journey, and the lyric essay form enabled me to approach that journey at a glancing angle, taking better care of myself and—I hope—the reader than would be typically otherwise available in more traditional forms of the personal essay.

KW: I think in talking about your book, I½I, I need to talk about hieroglyphics, proto-literate symbols, Elisa Gabbert’s New York Times article on poets’ punctuation as superpower and Jorie Graham’s “gaps and ciphers.” Whew. Why? Because your book creates a system of “almost-meaning” that goes far beyond just words and the traditional yoke of syntax. The title of your book introduces your complex visual manipulation of words and letters that becomes another meaning-making language in the book through typography, white space, absence of punctuation, use of a visual “eye,” odd symbolic letters that my apparently ancient eyes cannot decipher, the parenthetical, and, for gosh sakes, even a dark black penultimate page that swallows every mirror, ray of light, hum of glass that shimmers throughout the book. That was a wonderful surprise. Where in the world did that weaving of this other kind of language with its own orthography come from? How did you invent it, develop it, use it, and why?

KI: The vertical slash in the book’s title was the first experimental punctuation mark to appear in the text and really take on a dramatic life of its own. Initially I used it as a stand-in for the mirror’s surface across which personal pronouns like “I” and “my” could be reflected and doubled. Long before I had a sense of the book’s narrative arc, I felt the vertical slash propelling the project forward. The pleasure of using punctuation in this unexpected way led me to the other methods you mention: parentheses, white space, text atop text, the appearance of an actual eye, etc. And the book’s black endsheets were part of the genius of Geoffrey Babbitt at Seneca Review Books and Jeff Clark, I|I’s designer. These methods helped me translate some of the text’s visual elements to sonic ones. It’s often surprising to folks hearing me read from the book for the first time because of the continued repetition of “I|I.” Initially it sounds like I’m stuttering, which is kind of wonderful in how it catches the listener, stutters their attention much in the same way the vertical slash does on the page. But being a lyric essay, it’s not just about the sound. I aim to have the text play with its visual characteristics like illusions play with sight, thereby revealing and resisting readers’ assumptions.

KW: So… let’s talk about intertextuality, cento-poetry, and notes. Endnotes. Your book has almost thirty numbered end notes and, within those end notes, are more notes. Not as footnotes the reader could readily access at the end of a page, but end notes, at the back of the book. As a matter of fact, nowhere in the text of your book do you indicate that a sentence or passage comes from or alludes to another source until the reader stumbles over those end notes. You’re giving your reader two different reading experiences here: the text as it stands alone (beautiful in itself) and the text buttressed by these multi-layered backstories and references to other poets and writers. How does the reader reconcile with the cento-poet’s gesture of taking ownership of text not theirs, of voices that seem in the first dive to be owned by the cento-poet and not “other”? I remember listening to a poet reading their poem and ending on such a beautiful, startling note, because, I realized later, that ending image belonged to another well-known and beloved poem. How did you find yourself maneuvering through the possible landmines of the cento-poetry gesture?

KI: I saw a tweet some years ago that made fun of poets who have lots of endnotes because it evinces self-importance, but oops—I love them. One of the first things I’ll do sometimes with a new poetry collection I’m reading is to flip to the endnotes and acknowledgements. You point to the cento, which first appears nearly a millennium ago; poetry has a long tradition of working with other texts. Instead of paraphrasing or quoting, incorporating outside language and endnoting it asks us to interrogate the way we incorporate information into our own daily thinking and being. What is creativity? What is ownership? What is new, really? Fundamentally, to write a book is to be in conversation with all books, which is such a gift. I wanted I|I to mirror outside language back to the reader. It was important to me to have other folks’ language in the book. As I write, “What I|I’m saying is that it’s not my|my language in my|my mouth. Words are reflections.” Every word has a history beneath it, and to write anything is to make a new, thin layer of that history. Alternatively, to write a word is to point to its history because every word in this book, in this interview was first said and written by someone else.

KW: MFA from Colorado State University, a couple of distinguished chapbooks, two of the big prizes for your first book, an editor for the Sugar House Review, and oh! an Academy of American Poetry prize throw in there somewhere along the line. What’s next?

KI: Thank you so much! The past couple years I’ve been mainly caring for my young daughter and dealing with all the transitions that come with new motherhood. I am slowly working on a poetry manuscript that takes up the true story of fourth-century female Christian pilgrim Egeria (which includes a cento!). My friend and former teacher, poet Mike Chitwood, told me my poems would become much shorter when I became a parent, and the vast majority of the poems in this manuscript are fewer than a dozen lines long. I’ve also been trying my hand at more essays, including one that’s forthcoming in a Torrey House Press anthology about the Great Salt Lake, edited by Michael McLane. I work best when I can keep more than one fire going, moving back and forth between them.