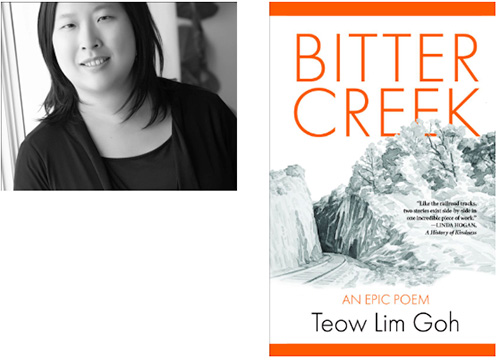

Teow Lim Goh

Writing Around The Archival Gaps: Teow Lim Goh on her new book, Bitter Creek: An Epic Poem (Torrey House Press,2025)

A poet, essayist, and book reviewer, Teow Lim Goh is the author of three poetry collections, Islanders (2016), Faraway Places (2021), and Bitter Creek (2025) and an essay collection Western Journeys (2022), which was a finalist for the 2023 Colorado Book Awards in Creative Nonfiction. Her work has been featured by The Colorado Public Radio, The New Yorker, and PBS Newshour. She is an MFA graduate of Western Colorado University .

KW: Congratulations, Teow, on your new book, Bitter Creek: An Epic Poem. I think if we surveyed the average person on the street on exactly what poetry is, we would find that a majority of people still define poetry in terms of the old Romantic poets of the late 18th and early 19th century: poetry about the poets themselves and their discoveries of a connection between their “interior world of feelings” and nature—what the most critical of poetry might call a very solipsistic endeavor. Yet, Bitter Creek, like your other three books, is very outward seeking. It's a journey into the events and people that led to the 1885 Rock Springs Massacre in Wyoming, when coal miners, spurned by the owners of the coal mines over wages, massacred twenty-eight Chinese immigrant coal miners and burned down their homes, destroying the Chinese section of town. Rather than tethering yourself to the personal lyric poem and your feelings, you chose to do extensive research and archival work before writing these poems. You “translate” much of your research into poems such as persona poems, found poems, and epistolary poems, as well as other formal structures. Thinking about the poets who perhaps have been wanting to write a collection of poems on a subject or event outside themselves, could you talk about the process of doing the research, discovering what matters to you, and then making that leap into poetry? What advice do you have?

TG: The personal lyric is one mode of writing poetry—I enjoy reading it, but apparently, it’s not how my brain works. My métier is the persona poem, where I can contend with the interiority of other lives. It can be used as a mask to explore subjects that are difficult to talk about directly. It can also be is a way of arriving at deeper truths about our shared humanity.

For Bitter Creek, I started with the archives—the Wyoming State Archives in Cheyenne, the American Heritage Center in Laramie, and the local museums in Rock Springs, Green River, and Evanston. There are plenty of records available—arrest and jail logs, telegrams between the Union Pacific and Wyoming Territory officials, the report from the Union Pacific’s investigations into the massacre. In the archives, I can figure out what is known and where the gaps are in the record.

In writing poetry, I can conjure around the gaps in the archive. There are no primary records such as letters and diary entries from the Chinese miners in Rock Springs. And the law was such that a Chinese person could not give eyewitness testimony against a white person, so investigators did not seek out their version of the story. I knew I wanted to center the Chinese perspective. As I explored the archives, I started to imagine a Chinese miner writing letters to his wife in China, but I didn’t invent him from whole cloth—I drew on the facts I could find about Chinese migrant workers in the late nineteenth century.

Not all gaps need to be filled. One of the unresolved questions is whether the Rock Springs Massacre was spontaneous or planned. There was a union meeting the night before the massacre, but no notes were recorded. There is strong circumstantial evidence but no definite proof that it was planned. I lay out the events as I know them from my research, including the contradictions I found in the archives, but I don’t speculate on this question. I don’t think I can do so ethically, and this absence doesn’t diminish the horrors of September 2, 1885.

For me, writing and research go hand in hand. And a lot of it looks like not doing anything—I sit with the stories and see what voices, angles, and emotions come to me. I also took a lot of naps. Often, I know I have the beginnings of a persona poem when I have a speaker and a situation that intrigues me.

My advice to poets is to listen for the unspoken stories in the world around you. It could be personal and introspective, or it could be about the larger forces of politics, society, and history. But what we don’t say, what we find difficult to say, is rich terrain for poetry.

KW: I have been reading your essays and interviews online about Bitter Creek and your other books of poems. I find your critical work quite brilliant in its understanding and articulation of prosody and form in poetry— not just your “factual” understanding, but your vision of how powerfully intrinsic the elements of sound, phrasing, and form can become to content. These elements become metaphor and symbol-maker in your work:

At one point in the writing of Bitter Creek, I thought of its structure as a kind of orchestration, a multiplicity of voices, forms, and styles coming together to give voice to something larger than each of them could do on their own. I saw the narrative passages, which I wrote mostly in blank verse, as the bass line, while the intimate first-person voice of the Chinese prostitute was the soprano solo. —from Bitter Creek: A Chinese Epic of the American West

Would you share with us the many decisions you made in creating this lyric epic poem? And why those decisions? And, lastly, what reader did you envision for this book? Poet? Everyman? Scholar? The poems read very simply and effortlessly, and yet after reading your essays about the writing of this book, the book has quite a subaqueous foundation. Can such intentional structure affect the unwitting?

TG: I detail my formal choices in the essay you cited from Diode Poetry Journal essay. I did not start out with the intention to write an epic poem, but rather, the form and structure came to me as I worked on the story. I’m not a strict formalist, but I’m interested in ways our structural choices expand the field of possibilities in poetry, the ways working with constraint can lead us to fresh ideas and insights. The story I tell is difficult, and form became a container in which I could grapple with its emotional complexities.

I tend to write for the interested general reader. After all, I seek to recover buried stories and bring them to light—limiting my audience to trained poets and scholars would defeat this purpose. Poets would recognize the craft decisions that went into my writing, and there are plenty of Easter eggs for literary scholars to scrutinize, but I also wanted to be legible. The story is ugly enough—I did not necessarily want my language to be beautiful, but I wanted it to be simple and clear.

In late August, I went to Rock Springs for the 140th Anniversary Commemoration of the massacre. Most of the attendees were not poets—they were descendants of the Chinese miners and merchants in Rock Springs, Chinese American community leaders and scholars, as well as local residents. I spoke about Bitter Creek and sold all the copies I brought. People kept telling me, “I’m not a poet, I don’t know anything about poetry, but I really enjoyed your book” – including a city councilman who had expressed skepticism about the memorial statue the city just unveiled.

A lot of labor goes into writing that reads effortlessly. The general reader might not notice my form and prosody choices, but they feel their emotional impact. That’s the power of craft. As I told the city councilman, “That means I did my job.”

As part of the commemoration, the city erected a monumental bronze sculpture at the Chinatown site, which is now a school playground, and held a dedication ceremony on September 2. In addition, archaeologists have been excavating the school playground and last year, they found the burn layer from the massacre. They have also been locating the descendants, most of whom only learned in the last two or three years about their personal connection to this history—including those who were born and raised in Rock Springs.

Poetry, which is rooted in the oral tradition, is one way to preserve and transmit history. Before the advent of written records, the repetitions of rhyme and meter were mnemonic devices. In Bitter Creek, I draw on this tradition and modernize it for our times. I created a polyphonic lyric text within an epic structure. The power of poetry is not just to channel facts and figures—the lyric, in particular, is a compelling way to convey emotions. I work with the historical framework and available evidence, but in writing poetry, I can also contend with the “interior world of feelings” of this history, the human foibles that culminated in atrocity.

Language is a powerful way to transmit stories, but it has its also limitations. In Rock Springs I saw the materiality of this history, the pottery shards and burned structures from the archaeological dig—there is power in the aura of artifacts. I talked to descendants, who carry this story in their blood and lineage, even if they did not always know it. And I listened to their stories, of growing up in Rock Springs, of parents who moved away from Rock Springs, of returning to Rock Springs to visit ancestral graves—they are the living legacies of this history.

And the Requiem sculpture—to mark a site with a seven-foot statue is to inscribe this history on the land. I was not a part of it, but there would have been plenty of discussions in the planning and execution of the statue, conversations in which the city had to reckon with this dark past. The dialogue is ongoing and hopefully will continue for generations to come. We always talk about never forgetting to the point of platitude, but without a deep moral reckoning, without facing our wounds and complicities, we can never truly move on.

KW: Four books in nine years—one a Colorado book award finalist in creative nonfiction—, essays, poems, critical writing published everywhere, readings, teaching at Lighthouse Writers and Hudson Valley Writers Center: what’s next?

TG: I’m still in the very early stages of my next project, but I envision it to be an exploration of the larger Chinese diaspora, based on family histories I have learned in the last four years, as well as archival research into public histories. The Chinese who came to the American West to work on the mines and railroads were part of the same mass migrations out of southern China as my ancestors who went to Southeast Asia to open the jungle.