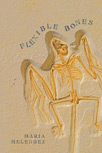

Sapo Dorado—A Recent Extinction

One thousand day-glo toads appeared in a handful of muddy seeps

that spring, los machos stretching their tiny orange suits

in a clamber to get at las hembras, who lay like glistening yellow

buddhas of the mud. No one knew the toad count from all

the Monteverde mountain-puddles together, but you just missed them.

A few years back, a couple cloud-forest kilometers higher,

you almost could've touched them. They were just here.

Back through a little drizzle and fizz of time, you'll find a writhing "toad ball," ten

males throwing their two-inch selves all over

a female's softball-sized back, slapping and shoving each other,

wanting to live, as much as they want the next guy

to get nailed by a bird. Don't be fooled by the females'

sanguine refusal to rouse themselves, their sedentary meditation

amidst the frenzy. They want to live, too. They spool this want

through their perfect insides, globe it to tan and black pearls,

sphere it out to the fates. They've made enough spawn,

so their natural histories say, for each clutch to withstand

depredation and still live on. Squirt-and-go parenting's

no less urgent than what passes, in our case, for nurture, mind you—

if the Maker had ordained teacher conferencing and soccer game

snack rotations for Bufo species, they'd carefully mark

calendars, insist their little ones practice goal-kicks,

and they'd read aloud twenty minutes each night to support

the tadpoles' fluency. But such is not their strategy.

After a blazing crossfire of the sexes, the golden toads

plowed back into mud. The next green season eleven

came out, the year after, only one. Stretch your fingers into

the drifting mist and you'll almost touch him, the last

sapo dorado, spotted a little ways higher, a year or two back.

(Sugar House Review; Poetry Daily)