The Colorado Poet, #16, Fall 2011

Inside issue #16:

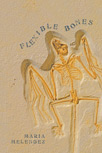

Flexible Bones: Melendez

Bob King: I noticed a piece by you on the website of the Poetry Society of America. Let me quote the opening: “Breath is my first language, ‘American’ second. I am a U. S. poet only now and then—when work spins out to engage some nation-high power. Do I foresee a day when poetry will be judged not by the color of its skin, but by the content of its characters? !Ojala que no! I don’t wish to be post-Latino and sans history.”

For those of us who haven’t been very knowledgeable about such issues—okay, for me—what’s the issue or concern you’re speaking to here?

For those of us who haven’t been very knowledgeable about such issues—okay, for me—what’s the issue or concern you’re speaking to here?

Maria Melendez: I was among a group of poets asked to respond to the question, “What’s American about American poetry?” Among my identities are “Chicana” and “bioregionalist” and “human being,” so I was trying to express that I only engage a “U.S.”-based identity when I’m writing about issues that engage the national concept of a “U.S.” On the other hand, I’m an “American” poet much of the time, as I regularly write about the land (including the people!) of the americas.

BK: So you must have wanted to engage some nation-high power in the pages of Flexible Bones.

MM: That’s for sure!

BK: This is your third book—what caused it to come into being?

MM: Several streams of poetic interest converge in this book—I was trying to be more personal AND more political AND more linguistically flexible, all at the same time. Not because I consciously found these aims to be interrelated, but because these were all directions from which siren-muses called.

BK: I find a tremendous variety of experimentation in your work, or is it just good spirits? The opening poem uses a rhythmic sing-song that made me smile. It starts “There’s a ghost, ghost, ghost/ in my navel, navel, navel, / there’s a ghost, ghost, ghost / in my bridge.” And you keep up that rhythm throughout. One poem later, “Ars Poetica: Autumn Packing List,” follows the same syntactic rhythm: “A flock of meetings / A threat of oranges A moon of matings / A crate of bells.” And that continues. You have a sonnet, prose poems, poems typographically like news stories, poems in two columns, left-margin poems and others that spread out over the page. What brings about this experimentation? Or “variety of form,” maybe I should say.

My natural inclination is toward mimicry and re-making rather than invention.

MM: My natural inclination is toward mimicry and re-making, rather than invention—I love taking up pre-existing forms, phrases, beats, etc., and pulling and stretching them to learn about their power and potential. I am also inclined toward aesthetic variety, as a writer, reader, movie-goer, clothes-wearer, etc.

BK: A couple of internet comments have said how important it was to hear you read, that you’re a wonderful performer of your work. This isn’t hard to imagine, given that the rhythmic and emotional tones are so strong in your work. Do you read aloud while you write? As you revise? Does that make a difference?

MM: When I read aloud as part of the revision process, it comes at a late stage—early- and mid-process drafts are being tuned to the sounds and rhythms I track internally, or from the beyond...reading aloud to myself can be useful as I’m testing the final tensions on the strings, as it were. Reading in front of an audience is a distinct, and incredibly useful, step in this evaluative process.

BK: I find your work quite strong in its seriousness as well as full of comic touches. And sometimes you play them against each other in two lines. I’m thinking of the opening of “Untitled”: “Everywhere, I am talked to by silence. / Who do you think you’re kidding?—it says / And—Chrissakes, give me a break. / Apparently, silence has no problem swearing.” Another poem, “The Skull of Arlen Siu,” deals with that early martyr of the Sandinista movement and is followed by a poem comic even in its title: “Goodling Guadalupe.” How do you see these two poles of the serious and the comic operating in your work and/or life? Or are they even poles?

MM: People may have the capacity for great gravitas and great glee coexisting within them at any given time, but it took some studied getting-out-of-my-own-way to let the gleefulness come through in this book. Readers and listeners regularly express gratitude for my having offered work in both registers, and listener/reader reactions are important for the development of my new work.