The Colorado Poet, #19, Summer 2012

Inside this Issue:

Move It or Lose It:

by Martin Balgach

These days, many of us feel like cosmonauts orbiting an era of hyperbolic digitalization, seemingly infinite bandwidth, and awe-inspiring technologies that boast space-age ingenuity vis-à-vis a pre-determined essence of almost-antiquation. We’re living in a world that redefines itself overnight; so it’s easy to nurture a curmudgeonly preoccupation with mourning “what once was.”

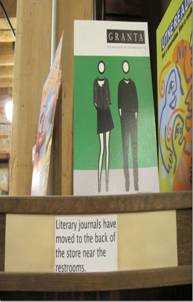

(from Numéro Cinq; Photo by Pedro)

But for those inflicted by the age-old, pen-to-paper desire to transcribe our hearts and guts into stories and poems and essays, we must adapt or face extinction. Friends, the literary journals have moved to the back of the store near the restrooms. Yes, ostensibly, it’s a bleak testament to the viability of our craft, but the future is rewriting itself before our eyes and I’ve decided to become part of the story.

As a longtime writer and relative newcomer to publishing, I’ve been sending out work for a few years, hundreds and hundreds of submissions to journals of all creeds and colors, from

the esoterically academic, to the newly crowned cool kids and the autonomously avant-garde. After mounds of rejection, I have finally enjoyed a modicum of “success,” having seen my poems published in print and online. And do you want to know the truth? I’m rather enjoying the electronic venues: they get read, a lot, by lit snobs and family, by Facebook friends and co-workers who equate poetry with rhyme, by strangers and who-knows-how-many-more virtual viewers.

Sure, whose eyes don’t get fatigued by a computer screen’s mechanized glare? I’ll admit it—my online reading attention span is shorter than its print counterpart. But regardless of medium, as a reader, I like instantly accessing great poems, essays, and stories. And as a writer, I appreciate having an editor respond to me in a few weeks or months, agreeing to publish a piece, to give it an audience, to make it part of a collective vision and creative endeavor. I want to participate in an artistic community, to have my work become an integral component of a crated statement. Yes, I like seeing my poems sharing pages with low-if indie rock tunes, color-soaked digitized paintings or photographs, all these consciousnesses breathing the same pixilated air.

I was fortunate to recently have a poem published in Fogged Clarity, an evocative online journal (with an annual print anthology component) that embodies editor Ben Evans’s vision that art, in its varied forms, represent a collective human experience, an emotional testament to our time. Fogged Clarity is easily one of the most vibrant, engaging, inclusive yet defined collections of contemporary creativity, music, literature, interviews, criticism, and thought on the scene. And content is added monthly! But don’t take my word for it, see for yourself—any of us can go there instantly, with a click: www.foggedclarity.com.

I’ve never believed any writer who claims that writing is primarily a personal endeavor.

I’ve never believed any writer who claims that writing is primarily a personal endeavor. Sure, the solitary satisfaction is part of the act’s cathartic charm, but it can’t be the ultimate aim. Intrinsically, writers want to be read. And in a world where art budgets have been slashed and paper, printing, and shipping costs are only sky rocketing, maybe it isn’t a tragedy to see struggling print journals transmuting into online entities, going away completely, or never gaining enough traction to even get off the ground. After all, isn’t survival of the fittest evolution’s integral denominator?

As a writer, would you rather have 10,000 monthly mouse-clicking readers discovering your work, or would you rather entrust your words, innermost observations, and professional expectations to half-torn USPS media mail packages clumsily arriving late to eight or nine hundred unknowable readers? Just this month I finally received author copies of a wonderful journal that accepted my poems in 2009. What year is it?

The new digital era is moving at a ghostly quick pace, so we must claim our vantage points. The world has redefined itself, so why not embrace the literary landscape’s evolution? The dynamic, healthy realm of online publishing is here, and we will not ever return to a pre-internet state. Isn’t Numéro Cinqo a dynamic testament to the contemporary scene’s vitality? In less than a year and a half, Douglas Glover has driven 200,000 hits to this robust blog / website / journal/ intellectual community playground, provoking and engaging newcomers, students, teachers, and thousands of other readers and thinkers. The playing field is on a cloud, and the staying power of the new thinking forums will only offer fresher contexts, deeper exposure, and dare I say—satisfaction?

Yes, of course, we can still covet our favorite print institutions, the ones who buck the uphill realities and fight to maintain their mission of the traditional hold-it-in-your hands print experience. And I know dear e-reader, I will also continue to optimistically fondle photocopied, crookedly cut rejection slips and my busted-pipe dreams of old school, printed validation. But the mediums no longer seem separate to me. More importantly, I don’t want to reinforce a close-minded, egotistically justified distinction between print and online publications. Each journal’s individual aesthetic, design, history, and mission are far more relevant than medium.

We have made some good progress here. I know, this is hard, emotional work. I too am a romantic. I have saved every print journal that I have ever bought or subscribed to. It’s like a micro-library showcasing years of literary and artistic movement, as well as my own changing interests and discoveries. In thirty or forty years, I’ll look back through those dog-eared volumes and see the early work of eventual giants—much in the same way, in a local used bookstore, a tattered 1950s copy of Evergreen Review, Volume 3, hangs in a plastic bag behind a cash register, Jackson Pollock’s cigarette-clenching hand waiting to be held and creased, contributors listed (in black and white) include: Camus, Beckett, Robbe-Grillet, O’Hara, and “others.”

But we writers are not in the business of creating artifacts. Human consciousness moves through words and ideas…

But we writers are not in the business of creating artifacts. Human consciousness moves through words and ideas, regardless if they surf bleach white waves of pulp or the tenacious, light-generating portals of computer screens. Human spirit gets conveyed either way, and these days, fonts, interactive design, and multi-media functionality are allowing for an even greater aesthetic impression to be woven into our words.

The unveiling of a standardized EPub3 file format is right around the corner—a “book” will no longer mean pages bound between covers, held in our hands. It will be a living breathing media entity. Already, much of our art is being disseminated, preserved, and coded for the ages by pseudo-omnipotent silicon chips, warmly vaulted in the grey plastic hum of seemingly invisible, dust-choked servers.

I know, I know. I don’t necessarily want it this way either. But what’s the use in resisting change, which is, after all, the first order of the universe? I mean cell phones have essentially destroyed introspection, quiet meals, the opportunity to browse a bookstore uninterrupted (I always thought library rules apply to bookstores?) but I’m not willing to give mine back, are you?

Technology and human advancement aren’t items on a buffet.

What I’m trying to say is this: technology and human advancement aren’t items on a buffet. Perhaps the challenge is to bravely accept that this world moves forward with our without our permission and acceptance. As individuals, we each reinvent and redefine ourselves, everyday, bridging and marrying new experiences to our memories of once-known things—so can we realistically expect anything but flux and evolution from our chaotic, majestic, impossibly mysterious world? The artistic future of human consciousness is happening digitally, and we can only choose how to reconcile our spirits and creative endeavors with the technologies that define and explain ourselves to each other.

By the way, back near the restrooms, you’ll also find the water fountain, a small selection of newspapers, the community bulletin board, outlets for washing and discarding, and whatever else you want to discover.

—

--Martin Balgach