Between the Sexual and the Spiritual:

A Journey of Faith

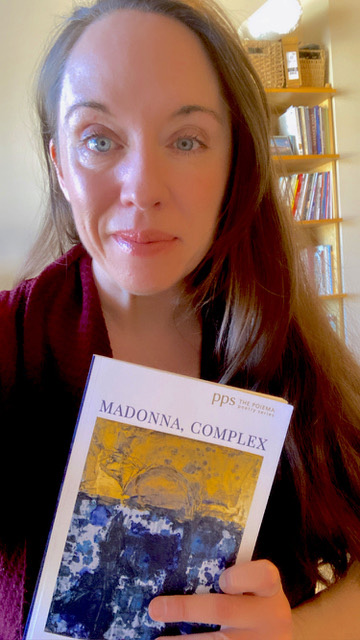

An Interview with Jennifer Stewart Fueston

on her first collection of poetry: Madonna,Complex (Cascade Books 2020)

Jennifer Stewart Fueston is a native of Colorado. She is the author of two previous chapbooks, Latch (River Glass Books 2019) and Visitations (Finishing Line Press 2015). Her current full poetry collection, Madonna, Complex, which she fondly refers to as her “pandemic baby,” was published in 2020 by Cascade Books. Her work has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net and been published in distinguished journals such as Agni and Western Humanities Review. Raised as an evangelical in the 1990s, Fueston has traveled world-wide, taught writing internationally and at home for CU Boulder, and served as editor and reader.

Jennifer Stewart Fueston is a native of Colorado. She is the author of two previous chapbooks, Latch (River Glass Books 2019) and Visitations (Finishing Line Press 2015). Her current full poetry collection, Madonna, Complex, which she fondly refers to as her “pandemic baby,” was published in 2020 by Cascade Books. Her work has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net and been published in distinguished journals such as Agni and Western Humanities Review. Raised as an evangelical in the 1990s, Fueston has traveled world-wide, taught writing internationally and at home for CU Boulder, and served as editor and reader.

KW: From the very title of your book, Madonna, Complex, it’s very clear that we are entering the realm of religion, a “faith journey” as you call it in your interview with the magazine, Fathom. How do you write about the religious, or have the courage to write about what is perceived as the religious in a super cynical, eye-rolling society where, according to the Pew Research Center in 2021, about “three-in-ten U.S. adults (29%) make up the religious “none,” meaning that they either describe themselves as atheists, agnostics” or “nothing in particular when asked about their religious identities.” And you have to contend with some readers whose knee-jerk reactions to religious writing is that it is sentimental or cliched. According to Utmost Christian Writers, a poetry editor for religious publications was recently quoted in Christianity Today proclaiming that “every age has its bad poets, but the last quarter of the twentieth century seems to have spawned more of them than any other.” And yet, your book garnered some darn good reviews and interviews and its poems were placed in a number of highly sought-after poetry journals. What do you think makes your faith-based poetry, if I can call it that, stand out and what advice would you give a person of faith who wants to write poetry from the religious realm?

JSF: Leaving aside for the moment that the terms “faith” and “religion” are not entirely synonymous, and also leaving aside the fact that many of those of who, in 2021, might claim a religious identity of “none,” may have in the past (day, decade, lifetime) claimed a belonging in one, I think the best way I can answer this question is to consider what my 5-year-old asked me the other day. We were having our usual after-school snuggles with our kittens and he suddenly asked me, “Why do we exist?” To me, that is the only question. And that is the question that religious systems have attempted, for better or worse, to provide an answer to, or at the very least, a way of talking about meaning. My faith tradition has provided me with stories, myths, images and vocabulary with which to try to understand ineffable things. I love what the poet Katie Ford said in her interview with the Rumpus a couple years ago, in regards to the heavily Christian use of the term “kingdom” in her book If You Have to Go. She says of such terms, “I don’t think they should all be thrown away, simply because they’ve been misused, or burdened by patriarchy or whatever selfish motive new to cling to the power of theological language.”

I suppose my advice to writers who write from or within a faith tradition would be to understand the conversation they’re a part of, and who are the poets embracing such conversations. For me, that includes poets drawing from the Christian tradition, such as Marie Howe (Magdalene), Mary Syzbist (Incarnadine), Christian Wiman (Every Riven Thing), Mary Oliver (Thirst), and Franz Wright (God’s Silence), as well as poets drawing from other faiths, such as the Muslim inheritance of Leila Chatti (Deluge), and Kaveh Akbar (Calling a Wolf a Wolf), or Jewish-influenced Ilya Kaminsky (Deaf Republic). A guiding principle for me comes from the introduction of Upholding Mystery: An Anthology of Contemporary Christian Poetry (1997). Editor David Impastato explains, “postmodernism has ruled everything off-limits. It declares that we have only language, and a language of bias at that. All fabrications of language like poetry are equally suspect, but at the same time equally worthy of our investigation. In other words, nothing is off-limits, and the Christian poet today advances an appeal to scrutiny from the same equitable zero-point as any other member of the writing community.”

KW: Writing any collection of poetry is a challenging endeavor, but first books can be especially hard: so often the first time book author is trying to cobble together the best poems written to date over a span of time, poems which they may never have been conceived of as a collection. When I want to “madden” myself, I think about Louise Gluck winning a Pulitzer Prize for her beautiful collection, Wild Iris, back in 1992. If I remember correctly, she wrote that entire collection during either a six or twelve week residency. I envy that energy she must have felt writing those poems. I’m pretty sure it’s Edward Hirsch who once described a first poetry book as collection of a poet’s “greatest fifty hits.” Madonna, Complex is your first full-length poetry collection. Some of the poems from your two previous chapbooks, Visitations (Finishing Line Press 2015) and Latch (River Glass 2019), are part of Madonna, Complex. And, yet, unlike some first books, Madonna, Complex has that sense of a journey, of an emotional arc through time and experience. Can you talk a bit about your process of putting this book together and creating such a “wholistic” journey for the reader?

JSF: I remember reading that a poet has their whole life to write their first book, and then only a couple years to write the next one! So your question was certainly in mind when I was putting together the full-length collection. As you mentioned above, I did conceptualize the book as a faith journey and the book’s four sections chart an evolution through different ways of thinking and wrestling with the language and beliefs of my upbringing. While not all the poems in the first section are “innocent” or devotional in tone, certainly more of them in that section are earlier work. Likewise, the latter section does hold most of my new poems, with their more nuanced ways of seeing and speaking. That familiar narrative arc, innocence to doubt to wrestling to reintegration, is a common one in literature and provided a good framework into which I could slot my individual poems.

When I knew I had enough decent material to construct a full-length project, I spent some time reading over the pieces and looking for something that would tie them together, and also allow for a wide range of style and proficiency. A couple of the poems were almost two-decades old by the time they appeared in the book— next to poems I had written just months earlier! Having the “faith journey” framework in mind, I was then able to select specific poems from the two chapbooks alongside the newer unpublished work and arrange them into the 4-part structure. This also helped me see where gaps existed in the manuscript, so then I could write a few new individual poems that would help stitch together the whole.

KW: As I read through your poems, I started thinking about John Donne. Donne is known, among other things, for the wonderful “tongue in cheek” sexual banter in his poetry, (not to be a “reductivist” about it). I’m thinking of his poem, The Flea. And, then, there is the quite “unplayful” Holy Sonnet: Batter my heart, three-person’d God, in which the speaker uses the conceits of rape and battery to plead to God to fill him with the Holy Spirit. Your poems in Section II, which seem to center around the speaker “succumbing” to, what I’ll call, her lust, remind me of the tension between the ecstatic and the sexual that Donne creates and what is a major motif, especially in the lives of women saints and the ecstatic. For instance, your poem, “Iconography,” ends with these lines: “You become/a Chapel I kneel inside, mouth open: waiting/for whatever grace is laid upon my tongue.” What led you into this kind of “metaphorizing” of the sexual into the religious in this book? And did those conceits come easily to you or did you have to dig hard to find them?

JSF: Section II was what I mentally referred to as the “sexy” bit of the book when I was putting it together! That’s an oversimplification, of course, but the majority of the poems in that section (and continuing into the embodied experience of young motherhood in section III) have to do with questions about the place of the body alongside the spirit. It also represents the considerable wrestling with the evangelical “purity culture” that I and many people my age grew up with in the 90s. I talk quite a bit about this in the Fathom interview you reference above. In that religious context of my upbringing, sexuality and spirituality were often set up in opposition to one another. My poems here are arguing with that false dichotomy. The intentional use of sexual imagery and metaphor in the context of religious doubt and wrestling is part of my attempt to integrate these aspects of my life experience. As you mention, there is a decent tradition in well-known poets like Donne who navigate this territory. My guide in this area lately has been the work of Linda Gregg, whose poems are simultaneously deeply sensual and intensely spiritual.

KW: You love words; obviously. You love names of places, paintings, people. Yes, you’re a poet and don’t all poets, but you show a wide and beautiful vocabulary: tessellation, bougainvillea, lahmacun, satsuma. I guess I’m sensitive to this because I get that darn free “Grammarly” and, every week, it annoyingly “shares" a “report” on my “unique” word usage. Do your words just pop out as you write? Do you research words? Use a thesaurus? Give us some advice on how you find the “bread and butter” for your poems.

JSF: I don’t research words, and I try not to use a thesaurus much because I think if the word is unfamiliar to me, or something I have to reach too far for, it’s probably not the right word for the poem. That said, there are times when I’ll use a thesaurus because I want a synonym that meets the rhythmic demands of a line. The words you mention here are the kind of thing I pick up and jot down in my journal because they capture some specificity of a place. Naming things carefully is one of the primary jobs of a poet, I think. Many of the words that arrive in my poems come through traveling quite a bit in countries where English is not the primary language. Picking up specific names of plants, roads, foods, places feels to me like collecting souvenirs, just like keeping train tickets or postcards or pressing leaves into a journal. They’re evidence of having been somewhere.

KW: Two chapbooks and a first full collection of poetry. What’s happening next for you?

JSF: Theoretically, I am working on a second collection! It has been pandemic for two full years, though, and I have small children who spent most of 2020 & 2021 schooling at home with me, so I have given myself a lot of grace not to be very productive. I do have a unifying concept and a stash of more than two dozen poems that have been published already, so that’ll continue to grow until I feel like I have a manuscript worth sending out. In the meantime, I hope to keep supporting the literary arts in Colorado through serving on the Board of Directors for the beautiful literary journal, Ruminate, based in Ft. Collins. I had the chance to serve as editor for that journal for six months last year and that was a nourishing experience. I also do quite a bit of editing and collaboration with other poets on their manuscripts and serving as a poetry reader for the online journal, Whale Road Review, out of San Diego.

More of Jen’s poems can be found online at:

- "The Mother.” Thrush. January 2021

- “Poems With Lines From My Son.” Bracken. Spring 2021, issue VIII.

- “Fruit.” Phoebe Journal. May 14, 2021

- “On the morning of your anniversary.” Glass: A Journal of Poetry. January 2020.