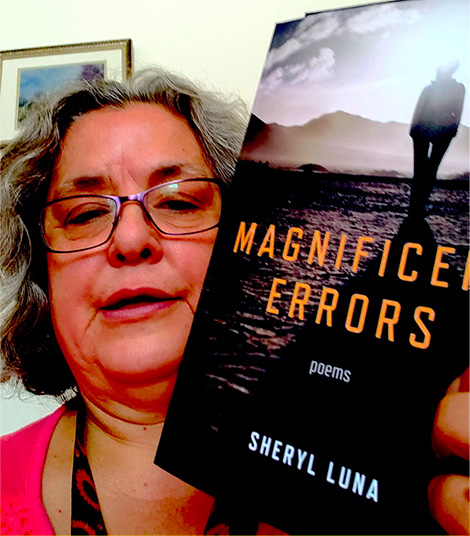

Into The Beautiful Rightness of Magnificent Errors, by Poet Sheryl Luna, winner of the 2020 Ernest Sandeen Poetry Prize.

Born and raised in El Paso, Texas, Sheryl Luna is a recipient of the Alfredo Cisneros del Moral Foundation Award and an inductee into the Texas Institute of Letters. Her poetry collections have won the Ernest Sandeen Poetry Prize and the Andres Montoya Poetry Prize and been finalists for the National Poetry Series and the Colorado Book Awards.

Born and raised in El Paso, Texas, Sheryl Luna is a recipient of the Alfredo Cisneros del Moral Foundation Award and an inductee into the Texas Institute of Letters. Her poetry collections have won the Ernest Sandeen Poetry Prize and the Andres Montoya Poetry Prize and been finalists for the National Poetry Series and the Colorado Book Awards.

KW: Sheryl, congratulations on Magnificent Errors, winning the 2020 Ernest Sandeen Poetry Prize. In your interview with the University of Notre Dame, you describe the book to be about “mental health issues,” and that it stems from your “experiences in transitional housing after being temporarily homeless.” Yes, absolutely. But I also have to say, “Not so fast, Sheryl!” The bedrock of the book is your own personal “houses” of madness (and I use “madness” because you have): a searing childhood sexual assault and the debilitating loss of, but, ultimately, discovery of a poet’s authentic voice, born and risen out of the ashes of what feels like, so sadly, personal shame.

But I’m not surprised. I know from my own experience how hard it is to break down that personal wall of silence after trauma. The ongoing “dis-authentication” of confessional poetry, especially women’s, is another roadblock. In 1965, it was argued that confessional poetry “tends to damage poetry.” In 2001, Alice Ostriker spoke out about the Language Poet’s abandonment of the lyric “I,” arguing that a “poetics that denies self is useless.” A recent article in VIDA: Women in Literary Arts explores the tabooization of confessionalism, especially feminine-voiced. Talk about the inward and outward pressures you experienced writing this book.

SL: I did feel a great deal of pressure not to write personally about myself, much less trauma, due to negative opinions about confessional poetry, which I heard a lot about in graduate school in the nineties. I feel that, along with anti-narrative sentiment, works to try to silence voices of people of color, women, and other marginalized groups. Even the word “confessional” sounds dramatic, too personal, and dismissive. One thinks of a private confessional rather than a public audience. I think change has hit the poetry world. There are a lot of grumblings about new voices and dismissive opinions about the craftmanship of such poets. Many such complaints do not address the vast majority of poets of color, women and LGBTQ poets. I couldn’t be happier about the changes in the poetry landscape. It is time new voices have appeared. I only hope there will be more changes and possibly a shift in power structures inside academia, as well as outside of it.

The fact is that those silenced voices have often experienced trauma due to the disparities in power structures. It is important for people to take back their power. I suppose that is what I was doing in the writing and the voicing of my traumas. Concepts embedded in patriarchy are finally being taken apart, and questioned, such as “universality.” A poem should try to reach as many people as possible, but the guise of universality has often been used to silence any questions to the existing power structures. Yes, finding one’s own voice and not succumbing to expectations of the establishment helps overcome the shame of trauma whether it be personal or cultural.

I suppose I said the book was about mental illness because there is such a negative stigma surrounding it. When it was time to look at potential covers for the book, many were depressive and dark. I wanted there to be a light. Recovery and healing is possible. I wanted that to be expressed. Naomi Shihab Nye once spoke of a man, a psychiatric patient, who hadn’t spoken in many years. She had asked the workshop participants to write about oranges, I believe, and, somehow, after many years of not speaking, the man began to talk. The image and the act of writing triggered a response. I am glad you mentioned language and madness. I feel the act of writing and creating something from nothing is an act of healing. The man found his silenced voice.

KW: As did you, Sheryl. Your writing reminds me of 19th Century Romantic Poetry and Buddhism. An interesting Ying and Yang. On one hand, there is an obsession with finding authentic personal voice that you introduce in the very first poem, “ Lowering Your Standards for Food Stamps.” Later in the book, language is “at times a burden” and “a colloquial riff.” I think of the Romantics because that obsession that damns you lightens in the book’s transformative moments: “Today, what’s found in/my voice,/music”. And that music, that voice, arises from the sublimeness of Nature. Yet, at the same “Buddhistic” time, that authentic voice isn’t of the Romantic “I,” but the “we,” outside of personal want. The third section of your book seems to center around this collective “we.” Have I grabbed on to something here?

SL: I am glad you mentioned Buddhism. I wouldn’t say I am an active practitioner, but I love Thich Nhat Hanh and have read many of his books. I do like to practice mindfulness on a walk or when sitting outside in nature. Nature is the central balm when it comes to healing. I suppose I do deflect from much of the trauma by reflecting on nature. I love the idea of impermanence and how all things are interrelated and connected.

When I first began writing poetry, I was reading the Romantics and Texas Woman’s University, so I believe that has also been a big influence on my poetry. I see Romanticism as very feminine. Our emotions can be part of the journey of creation. Again, there is this patriarchal idea that we should keep a lid on our emotions or distance ourselves from the emotive, which I think is okay to let go. I did feel the third section of the book was about a spiritual journey. The poems stem from a love of nature, and I hope they express that we are all interconnected, bound by a spark of life. The whole of humanity for me is like a wave from which we all are but a drop, and yet, simultaneously, the whole ocean. I find peace through the acts of observing both the internal world and the external world.

KW: Curandera shows up in the second poem of the collection, The Vocation, and keeps popping up throughout the book. Curandera is a folk healer or medicine man and it feels like she embodies you in these poems. Curandera’s presence feels deeply linked with why Magnificent Errors is made up of so many voices from your experience in transitional housing. Can you talk about how her presence and the stories of others made your story possible?

SL: Curandera comes early in the book. My great-grandmother and possibly my grandmother went to a Curandera or healer. My grandmother was born in Zacatecas, Mexico. I suppose it is from that ancestry that I came up with the term, rather than a shaman or priest or some other word. It seemed to express that silenced history I wanted to honor. The history of women and marginalized peoples. I was raised in El Paso, Texas, a predominantly Mexican and Mexican-American city. In grad school, many years ago I was told that “minority writers use mere reportage,” and lack skillful craftsmanship. I know that the men saying these things had not read much Mexican-American literature. I was told on more than one occasion that Chicano Literature was not real literature. I was told I could not do a dissertation on Latina writers. The men in my program had a great deal of confidence, tremendous confidence in their opinions about what is good art and what is bad art. I suppose that in the poem, “Curandera,” the men with fat towels around their shoulders wearing flip-flops are those old voices. Now, 25 years later, that cloak of invisibility, dismissiveness and shame is beginning to fall away. As for transitional housing, and the people I met there, they too are seeking a place to call home, a place of comfort, peace, and self-esteem. Thich Nhat Hanh has a small saying that he suggests we say during walking meditation. I think it is simply, “I have arrived” or/and “I am home.”

KW: Finally— multiple books along your career, major awards. What’s next for you?

SL: I have not written much during the pandemic and am hoping to begin writing again. I do have 180 pages of essays about myself and people who struggle with mental illness and homelessness. The essays deal with trauma. I have set them aside for years due to the unease I feel when it comes to reading them and revising them, so I am not sure if I will return to them or not, but I will see. I am interested in religious indoctrination and propaganda due to my family’s support of Donald Trump. I feel compelled to examine that and what seems an intense interest in fatalism or apocalyptic thought. For instance, my brother and cousin’s desire to buy guns to protect themselves “off the grid.” This has been on my mind with the continual mass shootings and the Uvalde and El Paso shootings in particular. They are all horrific and what it says about our culture is not good. I think hyper-religiosity, judgment and fear also stem from trauma.