An Interview with Rosemerry Wahtola Trommer

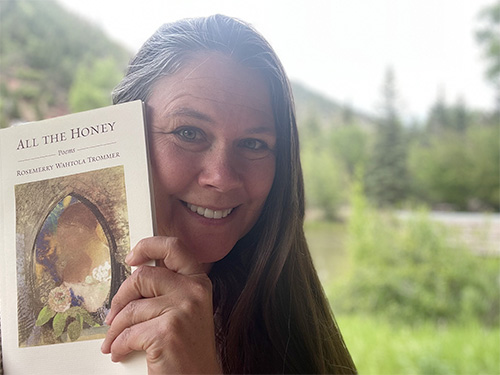

Rosemerry Wahtola Trommer has been a shining light on the Western Slope Poetry scene for decades. A community collaborator, passionate teacher, and beloved poet (check out her numbers, poets!), Trommer has just published her thirteenth volume of poetry. All The Honey is in its third —probably fourth by now!—reprint by Samara Press and garnered the honor of being the #1 Best Seller on Amazon New Releases.

KW: I think I have been hearing your name in the poetry world for years now—San Miguel County and Western Slope Poet Laureate, Telluride Writers Guild director, storyteller, performance poet, teacher, conference presenter, etc. You are so intricately involved in the Colorado poetry culture with some real enviable blasts from the “outside” world like Oprah’s O magazine, A Prairie Home Companion, PBS News Hour, American Life in Poetry and, for goodness sake’s, river rocks! (I want to write poems on rocks!) And, yet, you’ve done this outside the “grid” of the expected poet’s life: MA in English Language and Linguistics, but no MFA in poetry. No Ph.D. with creative dissertation. No tenure track teaching job in a “good” (I don’t know what that means really) creative writing program. Just the creation of a beautiful crazed tapestry of a vital life in poetry. As more humanities programs disappear and non-residency MFA programs proliferate without any real opportunities for college teaching experience, poets wonder how to make it in this narrowing world and still be part of the poetry community they love. What did you do and what advice can you give the rest of us?

RWT: I don’t think I’d heard of an MFA degree when I finished my master’s in 1994. Even if they existed, I doubt they would’ve let me in. I wasn’t a “good” poet. But I was devoted, wanting to learn, willing to work, ready to jump in and do anything to serve the poetry community. In the meantime, I worked as a journalist, freelancer and social worker.

Though writing poems is mostly a solitary act, I’ve been involved in the poetry community as participant, leader and collaborator, especially Columbine Poets, our state poetry society and Telluride Writers Guild, which I ran for ten years, and the Talking Gourds Poetry Club, which I co-hosted with Art Goodtimes. As director of the writer’s guild, I wrote grants to pay dozens of poets and writers from around the state to come teach and perform. This allowed me to connect with lots of poets, though I live quite remotely. Plus, I have traveled a lot doing hundreds of readings, performances and workshops. Years ago I served on the advisory board for the SPARROWS Poetry festival in Salida, and now I serve on the CPC board! If you’re willing to work for free, you can get A LOT of work! It’s great for gaining experience, relationships and confidence.

Not being part of an institution, I’ve found many other ways to share that poetry with the community: Poetry on the radio. In the schools. In restaurants. On social media. Poetry for online students, for hospice, for people in recovery, for mothers. Since the mid-90s, I have taught poetry classes at the local library and the local arts school. Man, did I study to teach those classes! I developed a deep love of research, which has fueled my practice.

In 2019, I left social work and now I teach and share poetry: for private students, art schools and spiritual organizations, businesses and nonprofits. And I’ve learned that collaboration is THE BEST! For instance, I have a podcast on creative process (Emerging Form) with science writer Christie Aschwanden. I lead monthly writing circles with therapist/mindfulness instructor Augusta Kantra. I lead meditation retreats with dharma teacher Susie Harrington. I lead writing programs with cultural historian Kayleen Asbo. These collaborations help make poetry feel relevant, even necessary, to people who normally wouldn’t connect with poetry. Plus, collaborating with other talented people is the most satisfying life I can imagine.

The best advice about poetry I ever got was from poet David Lee. He said, “Surround yourself with people who are better than you.” I’ve been so lucky to be surrounded by amazing poets, more than I can name here. It’s been everything.

KW: You reveal in your prelude to All The Honey that this book travels the vast grief of losing your son to his own hand and, then, of losing your father a short time later. At the same time, it follows your journey through unshaken love and faith in the world. Our US Poet Laureate Ada Limón in commenting on the continuing rise in the popularity of poetry suggests that “there is a certain recognition that poetry is in conversation with real, living humans on the other side of it, not just the academic side.” Surveys show that social media and web streaming have become major conduits for this poetry of conversation, which Limón attributes to a greater “acknowledgement of the reader on the poet’s part.” Your poetry is so attuned to its audience. I jotted down ways your poetry opens to audience: use of lists, repeated grammatical structures, transformation of everyday objects like erasers and Mr. Clean into non-head scratching metaphor. I see no heed to the old adage of “show, don’t tell.” How do you develop your poems to be part of that living conversation?

RWT: I do think of poems as part of a “living conversation,” a conversation with all other poets (and artists) across continents, cultures and centuries, all of us wondering what it means to be alive.

Because I write daily, I tend to write about daily things—gardening, parenting, commuting, making dinner, taking walks. I fully believe, as Mary Oliver writes in “Wild Geese,” “The world offers itself to your imagination,” and that goes for everything. Everything has something to teach us—and poems are for me a way to meet the world with enough curiosity to listen and learn from erasers, spatulas, even Mr. Clean.

I am so grateful for metaphors. They allow us to make sense of the world again and again. So that the way an earthworm aerates the soil becomes a way to see how I, too, might aerate dense grief through very slow movements—constrict, release. So that the sound of crickets might help me see how I, too, might meet the darkness with embodied song.

I think “show, don’t tell” is garbage. I like the practice of show AND tell. My favorite poems are bridges between the outer world of sensual experience (show) and the inner world of emotion and idea (tell). To meet both worlds in one poem is to do what we are asked to do as humans—live in both worlds at the same time.

The other adage I eschew: “Write what you know.” Then we are just reporting. I try to write into what I don’t know—opening to imagination, mystery and play. Then epiphany is possible. I love stepping over the edge of the known in poems—

KW: “Best Seller poetry book, actual living and working the life of a poet as a means for existence . . .what’s next for you?”

RWT: Audio!!!

On July 14, I have a new album coming out, “Dark Praise,” a collaboration with guitarist Steve Law. The fourteen tracks explore "endarkenment"—all the ways the dark invites us to revelation, sensuality, play, intimacy, dreams, meditation, receptivity, self-exploration and self-discovery. Each released track is a music video with surrealist art from fine art photographer Marisa S. White. You can find the videos on my youtube channel. You can download individual tracks or the album from Spotify, iTunes, and anywhere you get music.

Another audio project is a phone app, The Poetic Path, I launched in March with Ritual, a wellbeing app.. Every day I release a 5-7 minute program with a poem, conversation, and optional prompt for anyone’s own writing.

I thrill to get the poem off the page and into the ear, honoring poetry’s origins as an oral and aural art.