Death and Love in the Worlds of If and Maybe: Mark Irwin on Poetry and his newest book, Joyful Orphan.

KW: Reading your newest collection of poems, joyful orphan, got me thinking about the Deep Image and Lorca’s beautiful definition of where duende is: Through the empty archway a wind of the spirit enters, blowing insistently over the heads of the dead, in search of new landscapes and unknown accents: a wind with the odour of a child’s saliva, crushed grass, and medusa’s veil, announcing the endless baptism of freshly created things. Why? Because you seem so often to dance on the precipice of the seemingly irrational and the leaps you make, which should be just ridiculous, feel profound, deeply felt, deeply new. I like to think that these lines, from your poem, “All the tiny arrows,” say something about how you enter into poem-making: “a puff of wind/ seems to come after each brief comet, and the mind / is cleared of its weather—a dead friend— and I think how some poems / are like a good suicide. You can’t know too much / before you start…” Talk to us about your way of writing poetry and how poems come to you.

MI: Instead of deep image I prefer to think of shuffling images that keep digging after something I’m not sure of, but am drawn toward, mysteriously, perhaps the way I am

drawn toward certain animals.

Yes, I do like leaping and prefer skeletal narratives as opposed to complete ones. A lot of what we call the irrational is just a question of risk. Perhaps, the irrational is easier to pull off in painting since grammar and logic are replaced by color and image. I’m sure Edvard Munch’s painting The Scream appeared irrational to many until they were caught up in the desecration of the Industrial Revolution. Frida Kahlo’s Self-Portrait with Monkeys may appear irrational to some, until you see one monkey’s tail around her arm, another's paw on her breast. I like to believe they’re protecting her from something.

I’ve always loved painting and perhaps work like a painter at times. There’s a wonderful quote by the French critic Gilles Deleuze made in reference to the paintings of Francis Bacon: “Mystery lies in the irrationality with which you make appearance. If you don’t make mystery, you make illustration.” That says it all for me. Death and love reside in the worlds of if and maybe, uncertainty, and that’s the terrifying and beautiful thing about life.

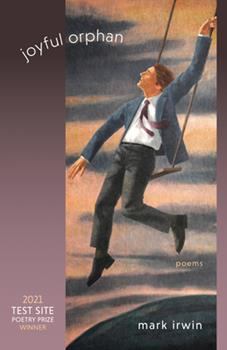

KW: Back in April, you did an event at CSU’s Gregory Allicar Museum of Art with the painter Ron Kroutel, who did the cover illustration for Joyful Orphan, on Time, Memory, and the Use of Materials. It seems that not only have you collaborated with a number of visual artists yourself, but you offer a class at USC called Forms of Seeing, Way of Listening that looks at the cross sections between poets, artists, and composers. How have collaborations with other artists contributed to your own work and why should a poet seek out such a collaboration?

MI: Yes, Ron is a wonderful painter and old friend. We met when I was the visiting poet at Ohio University back in the mid 90’s and Ron was running the painting department. Of course his paintings are steeped in mystery and what often appears irrational—and comical in a tragic way. Joyful Orphan sports his painting of a business man in suit and tie on a swing in mid-air, his face subtly erased by the sunset’s pollution as he looks up.

The title Time, Memory, & the Use of Materials comes from the title of a course I designed and taught with another wonderful painter, Enrique Martínez Celaya. We co- taught the course for poets, painters, and visual artists at the University of Southern California. I also taught at the Cleveland Institute of Art for several years back in the 80’s before I moved to the West, Colorado and California, where I divide my time.

And yes, Forms of Seeing, Ways of Listening is another course I teach, which integrates all the arts. I got the idea after walking once with the poet William Merwin. He’d heard a type of finch singing, and we walked till we saw it, (quite a long way, if I remember !) and then he said, Poetry begins with listening. He’s right, I think and we have to become still enough to hear that tiny voice within us?

KW: In Angie Este’s description of your earlier book, Shimmer, she says that these poems “couple the longing for radiance with the experience of grief and loss, both personal and global.” Your dedication for Joyful Orphan is global, calling out to the orphans of covid, ongoing wars, and our current Anthropocene Era. And, yet, the book has a deeply personal undercurrent: the death of your mother. And your subsequent meditation through the “debris of moments until each/of us becomes the one who enters memory, the one who has no age.” For those poets out there struggling to get out of the belly button, how, in writing your books, do you find your way into the global and out of the personal, yet still retain that deeply intimate sense of grief, of love, questioning, constant searching?

MI: I think the “longing for radiance” provides a transit in some ways from the personal to the global, for example, my poem “Nike of Samothrace.” I initially loved the beauty of the statue, the way the Parian marble absorbed the light, but the statue was stolen from Greece in 1863, so the magnificent, headless goddess of Victory is also presented as captive, a sad reminder of colonialism. Originally excavated by the French vice-consul and amateur archeologist Charles Champoiseau, she now rests atop The Louvre's Daru Staircase. The terrifying irony suggests that beauty may make us temporarily forget, but cannot hide the violence and dark secrets of history. —Secrets no different than the exploitations of capitalism where chic athletic shoes are assembled in foreign sweatshops.

A similar trope occurs in my poem “Library of Water,” which refers to the glass tubes

holding melted water from various glaciers in Iceland. Initially, I was attracted to the brilliant light within the tubes, but the poem, before ending on this aesthetic, note is a catalogue of psychological and physical pollution.

KW: A dozen books now? Ongoing and significant accolades (an aside: I do remember quite clearly mentioning your name in passing once and hearing a sudden shriek in the crowd: “Mark Irwin? He is the god of poetry!”). What’s next for you?

MI: Ha! Ha! on the “god” thing. I’ve failed too many times to qualify. Yehuda Amichai, the great Israeli poet, once told me in conversation that “the best poets are like soldiers fighting on the front lines in the trenches of language”! I’m currently finishing a new book that combines a sort of eco-poetics with the kind of personal loss we all feel through the ramifications of global warming. The book uses the ghost-voices of various animals while it also looks at war in a more mythical sense. The earth, which most artists consider as a sacred vessel, is merely—and sadly—a commodity to many others.

No one says it more persuasively than the poet W.S. Merwin:

I want to tell what the forests

were like

I will have to speak

in a forgotten language

Interview by Kathy Winograd