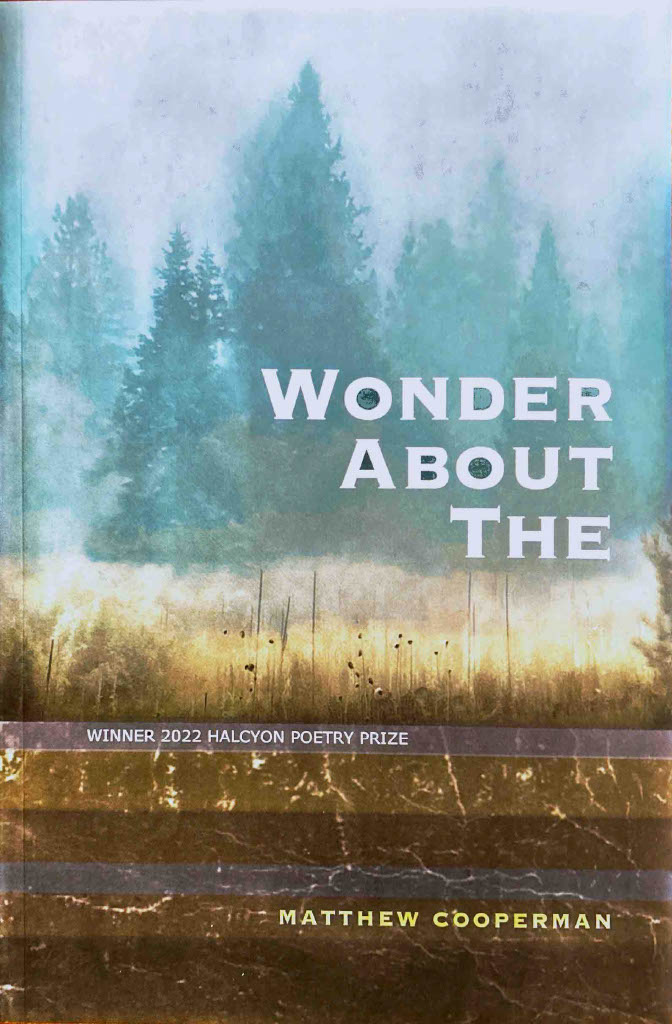

In Here and Everywhere: The Ecopoetics of Matthew Cooperman’s Wonder About The, Winner of the 2022 Halcyon Poetry prize.

Matthew Cooperman is the poetry editor at Colorado State University. His newest poetry book, Wonder About The, is the winner of the 2022 Halcyon Poetry prize (Middle Creek Publishing.) Cooperman has published numerous award-winning ecopoetry books and has received multiple pushcart prize nominations and awards such as the Jovanovitch Prize, an INTRO award from the Academy of America Poets and the Utah Wilderness Society Prize.

KW: Congratulations on your wonderful new book! I noticed that the poetry from Wonder About The has been published in ecotone: reimagining place and Big Energy Poets: Ecopoetry Thinks Climate Change. And Middle Creek Publishing describes itself as “The Literature of Human Ecology.” Since the ecopoem came to prominence, the nature poem has been given a bad rap or its become a shape shifter. With the most minimal poking around, I can find articles on “Why Ecopoetry?” and The Problem of Nature Writing and even a piece in Writer’s Digest on Contemplating Nature’s Changing Role in Poetry. Your poems arise out of the rivers of Colorado, so often, the Cache la Poudre River and contain a beautiful language of nature: “to call it bloom/celadon lichens skin to kin/or yellow flowering yarrow/ ranunculus watch it grow/fireweed and tansy . . .”. I have a hunch, after reading your beautiful poems, that you might have a lot to say about nature poetry versus ecopoetry and where you think your poems fit in the “canon” of things.

MC: In The Ecological Thought, philosopher Timothy Morton asks “how to awaken us from the dream that the world is about to end… because the end of the world has already occurred. We can be uncannily precise about the date. It was April 1784, when James Watt patented the steam engine, an act that commenced the depositing of carbon in Earth’s crust—namely, the inception of humanity as a geophysical force on a planetary scale.”

MC: In The Ecological Thought, philosopher Timothy Morton asks “how to awaken us from the dream that the world is about to end… because the end of the world has already occurred. We can be uncannily precise about the date. It was April 1784, when James Watt patented the steam engine, an act that commenced the depositing of carbon in Earth’s crust—namely, the inception of humanity as a geophysical force on a planetary scale.”

The dating of Morton’s “beginning of the end” corresponds rather uncannily with the rise of Romanticism, German, and then English. Wordsworth’s Lyrical Ballads announces in 1798 a new kind of poetry “really spoken by men.” And gender aside, it IS a revolution, simultaneously a psychological recognition of the individual as a ‘modern subject,’ the birth of much of the lyric poetry we still write today, and also a revolution of personal intuition of Spirt, “natural supernaturalism,” the visible signs of divinity or design in nature. But notice how that breakthrough signals a human recognition. Us seeing Nature. That’s the Nature Poem. However much nature serves as a subject, it is a reflection, revelation or relevance to humans. Hence personification. A good example is Frost’s wonderful poem “Birches,” which exhibits such meticulous observation: “They click upon themselves / As the breeze rises, and turn many-colored / As the stir cracks and crazes their enamel.” But the birches themselves serve as a metaphor for life cycles, for a wistful look back at a childhood of forest play, and a look forward “Toward heaven, till the tree could bear no more.” Trees, as such, are instrumental, not a subject in themselves.

Time moves on, and the question of the difference between a nature poem and ecopoem is, I think a question of the difference of centuries, or a creeping perspective, the inevitable consequences of the Industrial Revolution beginning to not only show up as the outward landscape but as the existential concerns of human psychology, even a geologic era: the Anthropocene. That is, the ecopoem moves from “out there” to “in here.” And the in here turns out to be everywhere. We suddenly realize the more-than-human-world has been there all along, watching or not watching, depending on your senses of animacy, but certainly with a myriad of realities other than human. Hence the suspicion of personification. To see the world itself. The ecopoem tries to enter that mystery.

While a bit prescriptive, John Shoptaw’s observations are very useful—that the ecopoem has to actually be about the environment, not just a backdrop, and that it has to be environmentalist, actually concerned with the forces that shape the environmental condition that happens to be our own. And perhaps find some way to ameliorate the damage. Brian Teare’s Doomstead Days is a great book of ecopoems. Brian is always in the poems, looking, listening, walking mostly, but his walking picks up the reality of the more-than-human world in striking ways that reveal how shot through the world is, say, with chemicals, oil.

KW: So the very title of your book, Wonder About The, gives a hint that “Here be Dragons” in the structural and typographical “maps” of your poems. No periods (am I right!?), select words that are in a different colored ink, bold faced and gigantus lines, drunken stanzas that tip over, lines that are slashes ////, erasure poems. Interesting enough, the most “traditional” poem forms with steadfast stanzas occur in the Wonder About The section of your book (which actually,” in another life,” as you put it, won a prize as a chapbook for a too soon defunct chapbook publisher, Pavement Saw Press). Give us your take on form in poetry, specifically what seems to be organic form.

MC: I’m revealing my age, but I’ve always been struck with the edict from Robert Creeley that “Form is never more than an extension of content.” Denise Levertov, whose essay “Notes on Organic Form” is still one of the best statements on the subject, revises that importantly to say “Form is never more than a revelation of content,” which gets awe, divinity, wonder into the equation. And that’s how I’ve tried to approach form in Wonder About The. To find a form that reveals both the threat and violence of the place, but also the wonder, the beauty, the color.

The title of the book comes from Theodore Enslin, a Black Mountain outlier poet, and one of our great walking poets. He wrote over 100 books, and many are derived from daily walks. So that center section reflects a lot of hiking up and down the Cache la Poudre “getting to know” my home slice, honing my sensorium. Much of this came out sub rosa in Spool, my 2016 book, where the backstory, or back landscape, was the Poudre to the drama, which was parenting a special needs kiddo, which was no time to write, but time to (still) carry her on my back, and so it was to learn to count as I walked, and write as I walked. So the river became not just a landscape of attention but a lifeline, a thread (and threat) of articulation that kept and keeps us alive. And so back to your first question about nature poetry versus ecopoetry. The organic form of Wonder About The resembles forms of the river, its shapes and sites of survival. And in bringing attention to the those shapes and sites it hopes to be environmentalist.

KW: Your book is not just a book of poems, but it’s a picture book. My own is coming out in March, so I found myself particularly curious about how you used visual images or photographs in your book and why. Text and image seems to be something you have been interested in for quite awhile: for instance, you did a text + image collaboration Imago for the Fallen World w Marius Lehene in 2013. The poet Robert Bly once said about the difference between the picture and the image:

An image and a picture differ in that the image, being the natural speech

of the imagination, can not be drawn from or inserted back into the real world.

It is an animal native to the imagination.

So, if poems do, and I think they do, alter reality, why the juxtaposition of poem and photograph? Hasn’t the poem already irreversibly transformed whatever “real” moment and place the camera has turned into a digital imprint? Isn’t the image transformed by a poet, who can describe things like, “Look up for the guide stars that/might heron us home—," as you do, far more than just sufficient? Why the need to share with readers what is mechanically captured in a little black box through a metal doohickey that simply opens and closes for light?

MC: You are astute in seeing the visual through line in my work. I have no hand skills, but I have a visual imagination. And visual art has always been an integral part of all of my books with the exception, maybe, of DaZE. And I love to collaborate. You mention Imago for the Fallen World, a collaboration with painter Marius Lehene. Perhaps my best friend at CSU, he also did the artwork on the cover of my 2011 book Still: of the Earth as the Ark which Does Not Move, and another chapbook. And NOS (disorder, not otherwise specified), which I co-wrote with my wife, the amazing poet Aby Kaupang, is filled with all sorts of graphic material that explore the “architecture of care” around neurodivergence. So the visual is hardwired into my sense of poetry.

But your question is why photographs? I think of Wonder About The as having a number of levels or registers, and one is docupoetics. I want to document the challenges of the river, to locate it in a photograph of the actual place, or see a map, or something graphic that embodiment. But I’m also interested in exploring a specific place, a specific palette that induces awe, wonder, care. So beauty (and threat) are inextricable from ethics. As Aldo Leopold said, “We can be ethical only in relation to what we can see, feel, understand, or otherwise have faith in.” I’m extremely lucky to live in a beautiful place. My hope is that the photographs extend that affective horizon. The book is an invitation to the people who know the Cache la Poudre bioregion to see it with all their heart, brain, eye, love, color and protest.

KW: Distinguished publications, multiple books, poetry editor of the Colorado Review, professor of English at CSU: what’s next for you?

MC: Wonder as reason, being interested; wonder as the sublime, looking for awe, all of it. Trying to keep writing. As co-parent of a special needs kiddo, my wife and I have our hands full. So to just keep going, keep teaching, and not succumb the despair of our messed up world.

I’ve got a few projects culminating right now—a new book with Free Verse Editions/Parlor Press, called the atmosphere is not a perfume it is odorless (which is Whitman) in 2024; and hopefully another book in 2024, or early 2025, with Station Hill Press called Time, & Its Monument. That’s a wildly ekphrastic and collaborative book with the Italian artist Simonetta Moro and the painter/poet Peter Richards. So more of my visual obsessions.

I’m also at work on a book of criticism on the poet Ed Dorn––“rather a thorn in the side of a more careful world”––who was my mentor at CU during my Masters. That’s pretty far along, and I’m also (still) at work on my twenty-plus year interview project Questioning (the) Witness: Interviews in Poetry and Poetics. Someday hopefully I’ll decide to finish that.