In-Between with the Ghosts Who Knock: An Interview with Hillary Leftwich on Heartbreak, Shape-Shifting, and the Lyric Essay

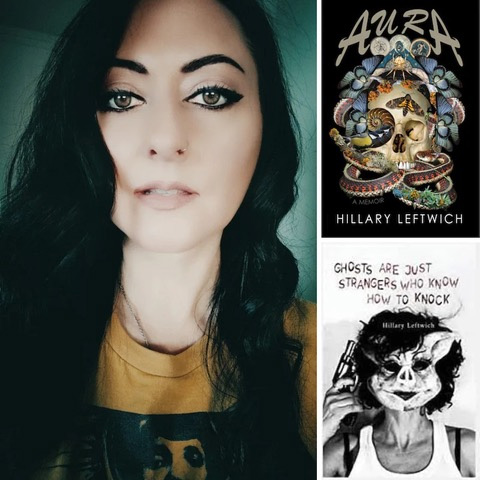

Hillary Leftwich (she/her) is a neurodivergent writer and author of Ghosts Are Just Strangers Who Know How to Knock (Agape Editions, 2023, 2nd edition) and Aura (Future Tense Books and Blackstone Audio Publishing, 2022). She owns Alchemy Author Services and Writing Workshop and teaches writing at several universities and colleges along with Lighthouse Writers, a local nonprofit for adults and youth. She focuses her writing on class struggle, single motherhood, trauma, mental illness, the supernatural, ritual, and the impact of neurological disease. Find her www.hillaryleftwich.com.

KW: The acknowledgment for your book, Ghosts Are Just Strangers Who Know How to Knock, identifies these pieces as “poems,” and, yet, this book won Entropy’s Best Fiction Book (2019). Here we are again, where I so often am in doing these interviews for Colorado Poets Center, in the genre-blur of prose and poetry, here, I’ll say flash fiction and prose poem. On the Brevity Blog, which seems like an apropos place to go since Brevity is a “journal of concise literary nonfiction,” two poet/essayists look at “Prose, Poetry, or In-between.” Among other insights, they offer the idea that poetry is a “spiraling in,” while “prose compels the reader to move forward.” They also quote the poet Julie Carr, who broadens their genre-suppositions: poetry is about “present time,” while to “write about the past and present is to write essay.” I find all those definitions applicable to what I found in your book. The vast majority of your pieces have narrative that pushes the reader forward, yet, time and again, that story-telling motion is chopped off by a swerving toward the spiraling in of poetry: often in the form of memory or through surrealism’s image-making. I still have whiplash leaping between bits of story narrative in The Difference Between A Raven and A Crow and then landing in a crescendo of image juxtaposed against image: baby scream, grandmother dying, raven hit “head-on,” wildfire, rain, drowning, crows . . .whew! I love it, but I am dizzy! Poetry, prose, flash fiction, surrealism: what is your “in-between” and how do you find it in your process of writing?

HL: I love all the insights you gathered, most especially Julie Carr, who I adore. She is one of many authors who I am influenced by, as you state, the in-between. I connect this space of in-between with my personal life which has transmuted my writing. Poetry was never a strength for me, at least not the form, but the imagery and language is something I think all writers took root from, no matter what the preferred genre. The lyric essay has a way of shifting itself, a shape shifter amongst words, that allows me to write without boundaries or rules based in traditional forms. It also comes down to resisting expectations from the reader. Traditionally, we know what to expect from genres, but what if we wrote outside of those boundaries? What are the possibilities? The process and the spaces where I write involve a lot of how words behave on the page. How they appear, what their function is, and use of experimentation to collaborate with these uses. Renee Gladman has always been an influence on me when it comes to being brave with form. Her blurring of drawings alongside words creates a somatic experience which I strive for—always trying to improve upon. We should always be evolving.

KW: I want to stay on this topic a bit more about the crossing over of poetry and prose, especially in the form of the lyric essay, which I think you are getting a reputation for in your writing and your teaching. I know that I’m a writer who moved from poetry to creative nonfiction and now so back and forth between the two that I don’t even try to identify what I am doing, because, as you say, the “in-between” feels like such fertile ground. Can you talk a bit about the lyric essay and what you’ve learned in learning to write it? And how you go about working with your students when you introduce them to the lyric essay? It’s still such a novelty, I think. Just last night, someone asked me about what creative nonfiction was and I found myself talking about the lyric essay, which lit up their eyes. For those poets who haven’t tried the journey to the lyric essay, the Eastern Iowa Review has some beautiful quotes from poets and prose writers on the lyric essay.

HL: During my MFA program I decided to add a concentration in poetry (aside from my fiction concentration) to better understand poetry and challenge myself. I never considered myself a poet and still am amazed at the way poetry manipulates space and language. But even after receiving my MFA and really connecting with prose poetry, I never allowed myself to experience more forms within my writing beyond that. Intimidation. But when I fell down the rabbit hole of the lyric essay and its many forms, I really started to educate myself on the uses of poetry within this writing form. I learned how to feel comfortable using poetic devices within the lyric essay and the buffer between the two worlds is what really built my confidence.

I tell my students when teaching the lyric essay that I can guarantee two things: they have already written the lyric essay form in some manner and just didn’t realize it, and labels are just another way of identifying something. It doesn’t mean it should limit your writing. Write what feels like needs to flow out of you and don’t give it a name until you feel sure you have said everything you need to say. The lyric essay offers a conduit within poetry; not something different. And poetry is something we discuss a lot in my workshops and classes. I try to help them sneak their way past what can be perceived as barriers to writing and understanding poetry within the forms of the lyric essay, most especially how it’s been used in writing historically for decades by writers of color and other groups that have had their voices silenced. Now, someone has put a label on this writing. It doesn’t mean it didn’t exist before.

I’m not big on rules or playing safe in writing. This doesn’t mean I’m experimental or related to anything perceived as rule-breaking. It just means, at least to me, that I feel comfortable trying new things but more importantly to be able to fail in these experiments. For example, working for four years now on an art collage/hermit crab essay I have failed to nail down over and over again, I finally decided to try a different route and still within this editing and creating process have discovered it’s okay to try new forms and not land precisely where you want. And I have flatlined in this manner so much. But anyone who understands that failure has always been part of growth knows that it’s stubbornness or refusal to give up that keeps us writing, not necessarily the accolades.

KW: Your book is a heartbreaker. The characters in your book, and I’ll call them characters though I have more to say about that, live so often dark lives, despite the brilliance of the specific things you, the author, give them in their lives: glass miniatures and orange Scouts and fawn-colored breast milk. They live those “lives of quiet desperation” we all fear in often bruising sociological and economic environments filled with death and murder, suicide or the lust for suicide. Here, characters are only safe “as roots buried beneath graves.” Any present moment, any present thing of this world, can dissolve into a maelstrom of remembered regret, despair, isolation, “a heaviness with no ending.” I don’t think I would be too forward to say, given your biography in the book, that what your characters experience and feel in this book are not so foreign to yours, perhaps. I ask this because I have always admired the essay by Brenda Miller, A Case Against Courage in Creative Nonfiction. She states that rather than applaud and write the “brave memoir” filled with “intimate details from the author’s life,” we should “shift our allegiance from experience itself, to the artifact we're making of that experience on the page. To do so, we mustn't find courage; we must, instead, become keenly interested in metaphor, image, syntax, and structure: all the stuff that comprises form.” Poetry, as you have named this book, is of the soul. How did you decide in writing these pieces what ghosts to give the reader, what to hold back, what to disguise, what to forge, hammer, and burnish?

HL: As writers we observe. We take note of the people and places around us. I have always wanted to give a voice to the people and places I experience, even if it makes the reader uncomfortable. Especially if it makes the reader uncomfortable. We can always choose to showcase ourselves as the hero of our own struggles. Writing allows us to change our stories, our experiences, whether this be in poetry or fiction or memoir. But what if? This question always came to me before the idea of turning Aura, my memoir, into a memoir. Before, it was a series of prose poems about my son and his epilepsy. But then the shape and purpose changed, and so did the meaning. Why bother to share and connect with readers if you aren’t exposing your true self? I knew, given the opportunity to have my work published, that it was important not to hide my background. I never thought the writing world would want to read about my experiences. What I chose to share, including pieces written about my previous jobs as a maid, private investigator, and working for the state, all had a huge impact on me. To be able to write about my past meant bringing honesty to the forefront, even if it portrays me as a homewrecker, a struggling single mother, and someone who has a hard time connecting with a world where I don’t know if I quite fit. This is what writing does for us. It allows us to share our ghosts with a reader in the hopes that maybe they can see our words beyond the page, beyond rationality, into that blurred, strange space with very little control over what shape it will become. A space where the living and the dead are indistinguishable.

KW: Two books, essays in many anthologies, including one to be published by Fulcrum, publications in multiple journals including The Sun and The Denver Quarterly, book reviews, scholarships from, among others, the Kenyon Review and Naropa, winner of the Reader’s Choice Review, teacher everywhere. . . and reader of the tarot and thrown bones! Whew! What’s next!?

HL: I never know what might come up, which is what I think a lot of creatives feel within their writing spaces and evolutions. Challenging myself with different genres and modes of composition is always something I enjoy, especially after writing within a certain form for a long period of time. I finished adding a drastic word count to a collection of mixed genre and lyrical essay forms that I had never been brave enough to consider before. This collection started out as small writing pieces that began in Zoom sessions during the pandemic with a close friend. After I finished this collection my brain (and heart) kind of broke. I put a lot into it and because of the content I need time to just heal a bit. I know I might be sounding a bit elusive but it’s only because the answer eludes me too. I’m open to seeing what might come next, whenever that might be.