Critical Commentary

Post-Modern Blues “issues from a warm and generous spirit whose playfulness amidst it all shines bright … we have been met with a rare gift.” [It is] “brave stuff … Perkins’ raw determination to call out in the lonely night and connect is as pure and hopeful an act of love as can be ... a wise and generous collection.”

—Marc Zegans, “Superpositions” in GLASS: A Journal of Poetry, January 28, 2022

“The poems of David M. Perkins arrive quietly but keep us alert to wonder. What a blessing to travel with a writer whose observations about life, love, and loss sparkle with clarity and wisdom.”

—Rigoberto González, author of 17 books of poetry and prose, winner of the American Book Award, the Lenore Marshall Prize in Poetry, and the Shelley Memorial Award from the Poetry Society of America.

“I May or May Not Love You teems with the language of living and loving that we can hold close without the dread of betrayal. His lines make the mundane significant, and we are always drawn into his work as if by a warm magic that we can trust. His is a modern romanticism chock full of allusion, metaphor, and the full force of narrative that takes harsh realities as they come … I applaud these poems’ capacity for love.”

—Jim Barnes is the author of 11 books of poetry and awarded the American Book Award and Pushcart Prize in Poetry.

Interview, OUTFRONT MAGAZINE

April 6, 2020

With Addison Herron-Wheeler, Editor-in-Chief

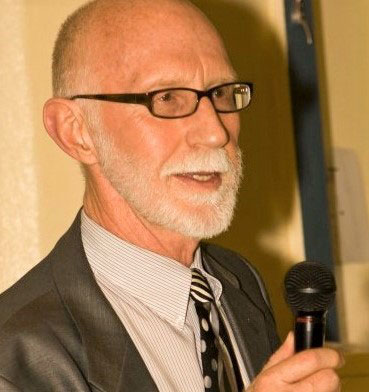

While the world is quarantined, it makes sense to pick up a good book. Local author David Perkins’ poetry in I May or May Not Love You is honest and relatable, as well as exquisitely executed. We chatted with him about his latest project.

When will your book be publicly released? Where will it be available for purchase?

The official publication date is April 2, my late sister’s birthday. You’ll find her in two of the poems, “The Goblins’ll Get You” and “Until Then, Then.” Valerie spent two terms with the Peace Corps in Thailand, met her husband there, and on their way back to the States, died from a severe allergic reaction to something in Nepal—no one knows what it was—and she was buried there in Pokhara. She was a great champion of my poetry, so it’s a kind of tribute.

The book is available through Amazon and Barnes & Noble of course, and then through other independent bookstores where the sales representatives have convinced the buyer it should be carried. I only know of a few, the reps’ travels are not over: Women and Children First and Unabridged Books in Chicago, Tattered Cover in Denver, Dragonfly Books, but it can always be ordered. I prefer people get it from their local bookstore as I once owned two bookstores myself in Denver; one on the west side of town, The Only Bookstore; and one on the east side of town, The Only (Other) Bookstore—or direct from the publisher, ICE CUBE PRESS because the publisher always takes the greatest risk—particularly with poetry!—and ordering direct from the publisher means more money in the publishers’ hands to spend on taking publication risks, like publishing poetry.

What inspired you to become a poet? Have you always been a poet?

Am I one? You tell me. History makes those judgments and I wouldn’t dare to presume. In my “Preface” I talk a bit about that: “I used it [“Poems”] on the cover … to gesture vaguely in the direction of something familiar.” When I think about them, afterward, I tend to think of them as being more like “wordscapes.” My mother was an award-winning artist, painter and sculptor, and I think, learning from her, is that what they are is using the magic of words, along with their meanings and their music, to try and paint a picture of ideas and feelings. You try to find the best possible words you can and try to put them in the best possible order to create a landscape of your thoughts and feelings and hope that others will recognize those and find themselves in the same place as you did when assembling them. Words are, language is, the most human thing we own, and the creation of a wordscape, a “poem” if you will, is the attempt, as E.M. Forster urged, “to connect” as human beings one to another.

I wanted to be able to paint, play music (you’ll notice that music has an important place in my writing) as a child—but I had absolutely no, zero, nada, zilch aptitude for either of those. But my mother, again, encouraged the reading of poetry when I was small. We would sit out on the front porch together and read poems out loud, everything from Ogden Nash to Robert Frost to Dame Edith Sitwell and laugh and share them and that’s I think where my love of words began, and then she encouraged me to try my own—and I’ve been trying ever since.

What is the process of writing a book like?

I never thought of writing a book, per se. It’s all I can do to think about just getting through a poem. The thought of a stretch of words going on and on for pages and pages is terrifying. I’ve attempted a couple of novels, but the energy that goes into that overwhelms me. The process of doing IMOMNLY was years in the works. In my case it was a lot of compiling, of editing, of rewriting, of sharing them with others and listening to their reactions, deciding which should live and which should die.

IMOMNLY was entirely serendipitous. A friend, Bruce Miller, who saw some of my work and with whom I had met while I was in book publishing (Running Press, University of Illinois Press, Georgetown University Press, and Oxford University Press (USA) among them), told me he really liked them, found them refreshingly different than the poetry that’s being published today, and that I ought to put together a manuscript. I told him he was bats, that no one would be interested, I didn’t have enough good ones, that my history in being published in journals/magazines was too scanty, and that (which we both knew from our publishing histories together) poetry doesn’t sell. He insisted and persisted though, and then he said that if I did put a manuscript together, he would personally take it around to publishers to try and place it. So I started going through my piles and files and folders and did and sent it off to him. I thought that would be the end of it, but within three months he found a publisher. No one could have been more amazed than I was.

Did you have any challenges throughout the creation of this collection?

The challenge is always the temptation to edit and re-edit, and rewrite where you think something can be better. And then I remembered something my mother once said, “It takes two people to create a work of art—someone to do it, and then someone to shoot them when they’re done.” Which is somewhat like what the poet Paul Valéry said, “A work is never truly completed … but abandoned.” So I wrapped the manuscript up, sent it off, and abandoned it.

How did you get in touch with a publisher and an illustrator?

My experience with the publisher is noted above. The illustrator, Jay Miller (no relation to Bruce), is an old friend from our days in Philadelphia together, and a terrific artist in all manner of representative art. He saw some of the poems, liked them and inspired, offered to create some illustrations to accompany some of them. His illustrations, which I love, have the taste of Vasily Kandinsky (the cover art is Free Curve to the Point – Accompanying Sound of Geometric Curves by Kandinsky) but folds it into a more representative style. Best of both worlds.

A lot of your poems are about love. What inspired them?

How much time do you have? Love is what this life is all about: family, friends, spouses, lovers, pets, music, paintings, sunsets, ideas, philosophy, poems, the sandwich you had for lunch, all the nouns. It’s also the most remarkable thing in our lives: it’s joy, exasperation, and heartache; it’s what makes you want to get out of bed in the morning, it’s what makes you want to take to bed forever; it’s the alpha and the omega. I have been lucky and cursed to be in love, I’ve been lucky and cursed to be loved; I love love and I hate love. It is the fire under the crucible of my poems, everything that’s breakable and everything that’s whole. It’s the unstoppable force and the immovable object. It’s science and history and religion, matter and anti-matter, it’s what holds us together and takes us apart. No writer can resist that subject.

What advice would you give to college students and other young people who want to be writers?

Do it. Read, read, read, and then write and then write some more; listen to others, but more importantly listen to yourself. And if it’s what you want to do, don’t do as I did and put it off in pursuit of some tenuous idea of financial security and some other kind of career—a cliché perhaps, but life is too short. And if you run into rejection, remember that rejection is just one person’s opinion, someone else will hear you and understand you. As Joseph Campbell said, “follow your bliss and don’t be afraid.”

What's the best part about being a writer?

For me, it’s finding exactly the right word in exactly the right phrase in exactly the right order that comes as close as I can to portraying the idea that haunts me.

What's the worst part about being a writer?

The worst part, about this book, is that my father passed away last August—and my mother and my younger sister and brother are gone now as well, so none of my family are here to greet it. But speaking of the craft and toil of writing, it’s the agony of wrestling over and over again with an idea or feeling that you want to capture in words and you know what it is; you can see it, touch it, feel it, taste it, almost hear it, but it takes hours and hours (sometimes days and weeks), stopping, going downstairs then back upstairs, diving again into the dictionary and then over to the thesaurus, a side-trip back up through the work to see where you’ve been and then down back down again tinkering along the way to nail down precisely what it is you want to say. But then, when it does finally happen, you get to the best part of being a writer.

Can you address the gay aspects of your book?

IMOMNLY is a life journey, so as a gay man, it’s a fully human one, as the great gay Walt Whitman said, “I am large, I contain multitudes.” The love poems in here, unrequited love, lost love, the yearning for love apply to everyone, although they were directed to men. There are specifically gay ones: “The Morning After the Walpurgisnacht Before” is the recounting of a wild night in the sexually-liberated 70’s (and here the legendary Denver dance bar, the Broadway; and its equally infamous baths, the Ballpark, were the scenes), and “Aging Out” deals with how an older gay man feels revisiting those bars. The poem, “Le Piano Zinc Bar, Paris” captures a pickup in a gay Paris bar—but moves into something I hope more universal. “Epilogue to a Moral Fable” was first published in the now legendary and first slick national gay magazine Christopher Street and deals with a topic dear to all gay hearts, Dorothy and the Wizard of Oz. Two poems deal with the great gay composer Tchaikovsky. and “The Last Days of Sebastian Melmoth” concerns Oscar Wilde in his Paris exile after his infamous trial and imprisonment.

I hope the poems will speak to anyone though, filtered as they are through a gay man’s sensibilities. When I grew up we were made to feel as outsiders, and that perspective never left me—but being an outsider makes one a keen observer of the world around you, I believe—and I think, I hope it helps to bring us all together in this one life we have to live on this beleaguered planet.