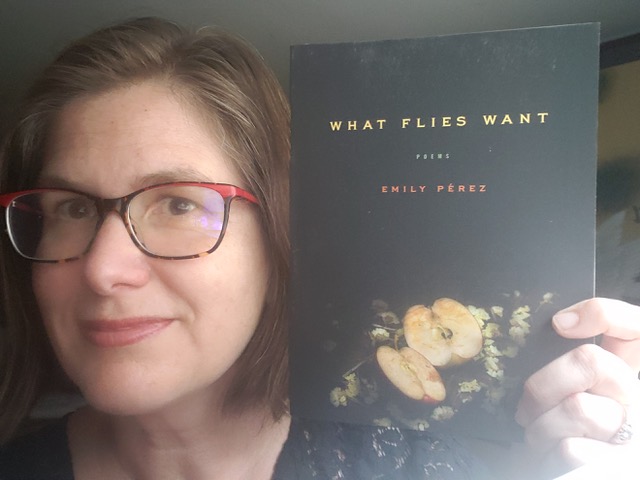

Hedgehogs, Singing Fingers, and the Architecture of Deeper Truths: An Interview with Poet Emily Perez on her new book, What Flies Want, winner of the Iowa Poetry Prize.

Emily Perez is the author of two poetry collections, including What Flies Want, winner of the Iowa Poetry Prize, and two chapbooks. She is also the co-editor of The Long Devotion: Poets Writing Motherhood. She is a graduate of Stanford University and the University of Houston’s MFA program where she served as poetry editor for Gulf Coast. Among other grants and fellowships, Perez is a CantoMundo fellow and Ledbury Critic.

Emily Perez is the author of two poetry collections, including What Flies Want, winner of the Iowa Poetry Prize, and two chapbooks. She is also the co-editor of The Long Devotion: Poets Writing Motherhood. She is a graduate of Stanford University and the University of Houston’s MFA program where she served as poetry editor for Gulf Coast. Among other grants and fellowships, Perez is a CantoMundo fellow and Ledbury Critic.

KW: I’ve come to learn that the big issues in creative nonfiction are truth and ethics. Philip Lopate writes a good essay on “The Ethics of Writing About Other People in Creative Nonfiction.” But poetry is so often about “making the world new,” “writing through intuition, metaphor, image, symbol,” and the poet as “speaker” in the poem—that truth and ethics figure differently. What Flies Want is a powerful, but not an easy book to read, nor, I imagine, to have written. In an earlier interview about What Flies Want, you discuss the difficulties during the time you wrote this book: familial mental illness, depression, marital disharmony, and crises in self-identification. Light and lyrical is not this book. One of your poems, “After Watching the Vampire Movie,” warns the reader against that misbegotten expectation. From your experience, how does a poet maneuver through the perilous switchbacks of writing about those they love?

EP: Writing about people you love is tricky ethical territory, for even if I, to quote Dickenson, “tell the truth but tell it slant,” moments in these poems map onto events in my real life, and readers may choose to read this as autobiography instead of art, no matter what the truth is. My struggles with mental health began in my teens. I had a mother who encouraged therapy, so I did seek help, but I kept my experience closely guarded. How might my teens and twenties have been different if I could have widened my support network and let go of shame? I’ve come to value openness about mental illness. Shame impedes treatment.

More recently, I felt very isolated navigating mental health issues as a wife and mother. These poems are only a slice of my life during that period, yet they represent what has been hardest to talk about. My hope is that someone who needs this book will find it and know they are not alone. These ideas, I hope, are not just moments of domestic drama, but connect larger explorations: how does mental illness intersect with violence? When raising children, how do parents undermine their own ideals? A recurring desire of the speaker in the book is to present a harmonious front through well kept secrets. And yet the book undermines that desire.

Through therapy and medication, my family moved through these crises. I would not publish anything I could not share with the people I love. My husband read the whole book a couple of times and really liked some of the most difficult poems. My children are trickier, as they were not old enough to consent to these poems. I conflate the two of them and events they experienced to veer away from their real lives. Someday when they read this I hope they will see truths about motherhood, marriage, and family, even if they don’t see the exact truths of their childhood.

Ultimately, the poem must do more than just tell a story from life; it must get at a deeper truth.

KW: I want to talk about Narrative arcs. The expression, “the arc of the book,” as a way of creating structure in poetry book is often thrown around as kind of short-hand for any organization that leads toward change and a sense of resolution (or not). Google how to organize a poetry book and “arc” appears in most every link. Yet, is the concept of the traditional “arc” outdated? Jorie Graham calls “narrative a deafening illusion. Life is a breath and a next breath masquerading as thought, meditation . . . .and worse of all as a thing capable of arriving at some kind of meaning, truth, conclusion.” Wallace Stevens said: “The poem of the mind in the act of finding /What will suffice.” And look where the postmodernist poets have taken poetry. I’m going to argue that traditional narrative arc doesn’t happen in your book! It remains pinned, finally, to a dark and chaotic world. Your last poem, “I Have Plenty,” reads almost like a hypnosis of quiet desperation: I am changed. Tell us your vision in this book and the process you went through in shaping it?

EP: This book started with a chapbook, Made and Unmade, published by Madhouse Press. Those 20+ poems about growing up female in a patriarchy consider issues of bodies, shame, and gendered violence. Many appear in the middle section of What Flies Want. I am a mother raising white sons, and as I asked myself how I was complicit in systems of patriarchy, racism, and gendered violence, I started to connect new poems to the poems in Made and Unmade. Other possibilities emerged, like the themes of mental illness. I live and teach in Colorado. My children grow up in a world of lockdown drills. What is the line between their play violence and actual violence? Every school shooter–most of them boys and men–is someone’s child. What was I teaching my own? What was I ignoring?

I had the fortune of running into a friend of mine, David Campos, at AWP in San Antonio. He suggested seeing my book as part of a genre and using the genre’s moves as a way to determine an order.* He later gave me great suggestions over Zoom about how to order the opening. You are writing horror, he said. You need a horror title. One of his ideas was What Flies Want, pulled from the title of a poem in the book called “What Flies Want is Not.” As soon as he said it, I knew it was right.

In terms of “arc,” I do lean on narrative exposition in the opening section–introducing the main characters and their issues. But I do not tell a story; I wanted to present this family and connect their domestic sphere to problems in the wider world. The arc is one of questions and problems that may get deeper, messier, but does not resolve. I see the speaker as more self-aware at the end, more clear on how she wants both control and denial. “I Have Plenty,” is an exercise in both: she may have more awareness but her control is a fantasy.

KW: In your collection, House of Sugar, House of Stone, you use Grimm’s folktales, especially the tale of Hansel and Gretel, as a metaphoric groundwork. Reading What Flies Want, I get “wisps” of mythology and folktale. Your notes allude to Grimms’ “The Robber Bridegroom” and Hans-My- Hedgehog. The poem, “How I Learned to Be A Girl,” has shades of Beauty and the Beast! Obviously, myth and folktale rock your boat. Talk about the role of mythology and folklore in your poetry. How do poems benefit when myth and folklore become vehicles for metaphor?

EP: I love using myth and folktale because they provide both architecture and associations, thereby saving me time and space. If the story is well known, as in “Hansel and Gretel,” I can jump right into the meditations without spending time on narrative. Also, tales facilitate the use of persona which provides a productive distance. Writing from the point of view of the step mother or the witch in “Hansel and Gretel” allowed me to explore feelings I had without the exposure of using a present day “I.”

When I wanted to explore parents abandoning their children, “Hansel and Gretel” supplied a model. And when I wanted to explore misogyny, “The Robber Bridegroom” provided a map of archetypes, complete with the patriarch, the groom, and even the woman who enables the robbers by feeding them. Add to that the magical elements–the singing finger!--and you have a mix of realism and strangeness perfect for a poem.

In many drafts in my notebooks, I play with the story but haven’t found the present-day hook. Hans-my-Hedgehog is a tale I did not read until I was an adult, and I knew I wanted to make use of it. I wrote several false starts about Hans riding a rooster and giving a map to the king. I eventually wrote a poem about motherhood that’s in the Fairy Tale Review called “Song for My Son,” in which I imagine the mother pregnant with a hedgehog. Later, when my real-life husband suddenly quit his career, the ending to the tale where Hans decides to immolate his quills, hoping to become a better match for his wife, presented itself as a good frame. Because Hans is a less familiar story, I told some of the narrative in the poem, but again, the narrative already existed. I just had to trace my world onto it.

KW: Two chapbooks, two full poetry collections, the Iowa Prize—where do you go next?

EP: I am working on another book of poems and hoping it finds a good home. I’m also trying to learn to write narrative nonfiction by reading books of essays and writing essayettes. Most of these pieces are failures, but I’m enjoying thinking about sentences, structure, and narrative tension in ways that I do not think about them in poetry.

*KW: also try Ordering the Storm: How to Put Together a Book of Poems