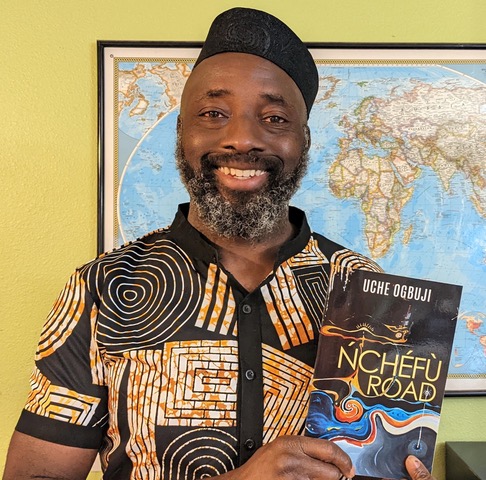

Tracking Down the “Global Nomad” of Nchefu Road, Winner of the 2022 Christopher Smart Prize—An Interview with Uche Ogbuji

Poet Uche Ogbuji is a Igbo-American immigrant from Nigeria, whose first full collection of poetry, Nchefu Road, won the Christopher Smart Prize. Ogbuji’s first chapbook, Ndewo, Colorado, won a 2014 Colorado Book Award and he is a 2022 Boulder County Arts Fellow. His work has been presented in places such as the CPR News, Blackbird Journal, About Place Journal, and Uncanny Magazine. A gifted musician and mixed media guru, Ogbuji can be found performing his work across Colorado and social media! (Just do a google.)

Poet Uche Ogbuji is a Igbo-American immigrant from Nigeria, whose first full collection of poetry, Nchefu Road, won the Christopher Smart Prize. Ogbuji’s first chapbook, Ndewo, Colorado, won a 2014 Colorado Book Award and he is a 2022 Boulder County Arts Fellow. His work has been presented in places such as the CPR News, Blackbird Journal, About Place Journal, and Uncanny Magazine. A gifted musician and mixed media guru, Ogbuji can be found performing his work across Colorado and social media! (Just do a google.)

KW: Uche, my first impression of Nchefu Road (I’ll loosely translate as Road of Forgetfulness) is “ This is a BIG book!”— fluidly moving between the familial and the political. You make no bones of this from the start. Your dedication is to your mother and father, and to the striking political figures of the Nigerian Civil war early in the post-colonial era of Nigeria. Your book brings to mind Carolyn Forche’s introduction to her anthology, “Against Forgetting,” in which she identifies the “poetry of witness,” which transcends the artificial boundary between personal and political poetry. Too often, young poets are taught to “write what they know,” learning that lesson so well that they cast a blind eye to the political and cultural world that surrounds them. Your book is a journey into discovery and remembrance, no matter how disillusioning in the present moment, and how that shaped you and continues to shape you. Talk to us about that journey in writing this book and the tapestry you’ve woven of the political and the personal.

UO: The title poem and a few others stem from versions written as a teenager, though they of course required a lot of work as my craft matured. My young self expressed how my emerging consciousness as an Igbo (though my father), a non-Igbo Biafran (though my mother), and an indoctrinated student of one-Nigeria policy (through my secondary education), all mixed uneasily with my lack of fluency in these cultures (thanks to my long absence while young and my primary education in the UK and USA). Moving back to the USA in my twenties, I felt compelled to write more about how I’ve spent my entire life feeling displaced, while consciously embracing that feeling. Indeed, though your loose translation of the book’s title works, an alternative is Road of Displacement.

I find much commonality with others of similar upbringings, fellow migrants of colonized origin, ricocheting around the world often despite meager means. We resonate in the complexity of our displacements, even where specific details differ. The same goes when I read novels by authors with such backgrounds. Recently terms such as Third Culture Kids and Global Nomads have emerged to describe this unintuitive group identity of non-identity.

Between the birth of my first child in 2000 and my fourth and final child in 2010, my time for poetry waned. I went through an entrepreneurial roller-coaster and spent most of my writing energy on computer tech articles for professional journals in order to supplement my income. This time served as incubation, with a lot of research and self-reflection, which made inevitable the mix of the personal and political you cite. By the time I started to get back to poetry, my complicated relationship to identity and the politics that shaped it was the topic that came on in torrents, growing into the shape of the present book.

KW: Your language, its musicality, your experimentation with form and, conversely, formalism. The Christopher Smart Prize judge, British poet Mel Pryor, was obviously bowled over by textuality of your poems: "but it's the words that sing, they soar and descend...I bow to them...I cling to them, I run them down." (Whoa! I think you have a fan.) You call your poems "a complication of Igbo culture, European Classicism, U.S. Mountain West setting, and Hip-Hop Music and Video." In your chapbook, Ndewo, Colorado, 2014 Colorado Book Award, you create a form you call, the "dialette." Thinking of my shadow poet lost in the sinkholes of poetry and, this time, stuck in repetitive phraseology, diction, and rhetorical structures, I wonder how you continue to be so experimental and what advice you might give my mythical poet.

UO: I’ve had to learn and relearn languages all my life, and I enjoy the feeling of only half grasping the meanings of things. I love to travel, especially to where the language is new to me, and I always challenge myself to learn what I can of it in the month or so before departing, at least for that twilight glimmer of understanding. I love to play with dialects and diction, adopting local accents as I move around. It’s not enough to have learned French in school; I’ve had a lot of time savoring the differences in French as spoken by immigrants in Parisian public housing, the streets of Marseilles, in Cotonou, Québec and Port au Prince. What about Engl-Ìgbò variations between Enugu and Owerri? How about the high speed evolution of Nigerian pidgin? As for English—ooh! From Chaucer’s proto-English through the Cavaliers and modernism (as written), through the colonized remnants from Singlish through Jamaican Patois (as spoken); modern UK and US dialects, including African-American vernaculars.

Readers of my poetry sometimes say: “you’re blowing my head off—So much language; so many changes!” To increase the chance that readers will persevere, I must offer something immediately worthwhile, so I work very hard on musicality, trying for idiom that just feels fun for the twirl on the tongue, for the tickle in the ear. I’ve always been interested in music, DJing as a teen, dabbling with instruments and singing. If I can get as much music as possible into the words themselves, perhaps the audience will have enough to enjoy that they spend the time to take on my work’s linguistic challenges.

I love fixed poetic form because of how the vine of creativity grows on its restrictions—the structures of music theory work the same way. Sure, some forms go stale over the centuries, but it’s a craft to freshen things up, including through invention, such as my dialette. Hip-Hop proves this fresh potential, turning antiques such as ballad meter into popular, global youth expression.

I advise poets to experiment with structure, even if they don’t ultimately use it in what they publish; more importantly, I advise them to read loads, including in dialects and languages that test them, and to memorize parts they like best. Radicals of mashed-up language are always knocking about in my memory, taking hold on wattles of verse structure.

KW: It’s pretty clear that if poets want to be part of the poetry world, they no longer can depend on that packet of poems tied with string to find its way into a publisher’s or reader’s tender hand, aka Emily Dickinson. (Okay, I exaggerate a tad: she did more to get her work out.) The gymnastics of social media responsibilities put upon a poet these days can be, to put it lightly, brutal! Yet let anyone land on your website and there is no doubt that you thrive in this digital world. You even have this lovely little audio clip for the totally clueless on how to pronounce the African names (yours included) and words you use in your poetry. Talk about that part of your poetic life— DJ, videographer, and all— and how it both nurtures and inspires your writing and career.

UO: Oh the real world is enough of a bargeful for any of us, never mind the endless expanse of cyberspace. I have the advantage of a technology expertise—knowing how the machine works helps me be a more efficient user—and I need all of this advantage in my often constrained time for the poetry and music I love so dearly. You can find many of the traces of Ńchéfù Road and my other artistic inquiries emerging alongside tech musings in the archives of Copia, the blog I maintained for a few years from around 2005. I’ve recently started a fortnightly dispatch in the spirit of that blog, The Loomiverse Times newsletter. I encourage you to subscribe, dear reader, if anything in this interview tickles your fancy.

The pandemic lockdowns saw me buying gear for DJing and software for music production, seeking to apply these in connection with poetry. I’m just releasing my first commercial (indie) music track, “Choccy’s Theme” [Link forthcoming]. It lies somewhat at the intersection of genres, so perhaps it will interest some readers. I‘m also working on music to complement Ńchéfù Road, and broader ideas for DJ sets that combine spoken word performance with traditional party rocking. For more on all this you can connect to my social media outlets through my Linktree page.

KW: A prize-winning chapbook and a prize-winning first full length poetry collection sure to garner more awards. What’s next for you?

UO: In addition to the multimedia projects I’ve mentioned above, I continue to write poetry, and I’ll soon assemble a manuscript of poems tapping into my afrofuturist interests. I’ve always felt that a life of displacements puts me in a unique position to ponder how displaced peoples might fare in our future, space traveling, climate stricken, technologically transformed, or otherwise. I feel I must do my part to ensure that my ancestral languages and cultures thrive in such futures. I have a lot of poems already on this theme. And I’m just releasing my first commercial (indie) music track, “Choccy’s Theme.”