Interview with Erin Block

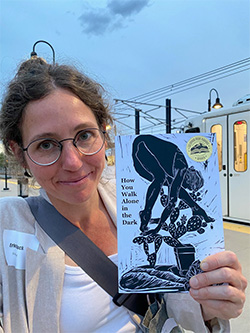

Surviving the Hunger: Erin Block on her new book, How You Walk Alone in the Dark, Winner of the 2024 Colorado Book Award for Poetry.

Erin Block is the Winner of the 2024 Colorado Book Award for Poetry. Her book, How You Walk Alone in the Dark, (Middle Creek Publishing) is also a 2024 WILLA Literary Award Finalist, her first book of poetry. She is also the author of The View from Coal Creek and By a Thread, a librarian, a freelance writer and editor-at-large. She lives in a cabin in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado where she hunts, forages, and gardens.

KW: You have already made your mark as a writer in outdoor sporting, publishing fiction and nonfiction in places like Midcurrent, Field & Stream, Fly Fisherman, and American Angler, as well as in more “literary” publications like The Rumpus and Columbia Review. You’re also editor at large for TROUT magazine. Your first book, View from Coal Creek, follows your journey making a bamboo flyfishing rod and your second book, By a Thread, meditates on women and fly tying. Your new poetry book, How You Walk Alone in The Dark, defines itself best in the web of your writing with these lines: “How does anything survive/the hunger of someone else./That’s what I ask/when I hunt.” These poems are bed rocked in nature, but certainly not the high lofty nature of the Romantics that so many poets still emulate: give me a scroungy jack rabbit in the bush and I’ll dress that bunny up in a pastel Easter bonnet in no time. (Kind of kidding.) Instead, you’re choking the life out of the rabbit because “a boot feels like cheating/not having to feel breath/move through fingers.” I think about the wonderful Beat poet Gary Snyder, a precursor of ecological and environmental poetry. His study of Zen and Japanese poetry forms like haiku so deeply informed his poetry that it became something beautifully “other” than simply nature or Beat poetry. Your decision to know “where some of [your] food was coming from” and to live in the mountains where that is possible has given a striking resonance to your poetry. Can you talk about the gifts and challenges you found in writing this collection of poetry as a prose writer, as a hunter, as a conservationist?

EB: I think when I started hunting, my life whittled down to specifics and my writing did too. Like the chiaroscuro style of the Renaissance, my field of sight narrowed, yet at the same time expanded. Small things mattered and big things faded into the background. I think it was a natural, although not completely conscious, movement away from longer-form writing to poetry. Poetry happens when there are stakes involved, and hunting is full of them. So, a real gift is that much of my subject and form is organically aligned.

It’s challenging to include conservation themes without becoming an environmental rally cry, which is not what I want for my poetry. But I do think it’s important to include the changes I see in nature (less bird song, altered animal movement and behavior, and so on) and the complexities of the gray mental space of never knowing who to root for—myself or the grouse, the bobcat or the pine squirrel, the deer or the lion. We’re all out there trying to feed ourselves and someone has to lose. This includes gardens, foraging, and plants too. When I pick a head of lettuce from my garden, I kill a thriving, living thing. We consume a lot of death to stay alive.

And it’s challenging to not shy away from the realities of nature (what those Romantic poets leave out), but at the same time give those realities meaning that aren’t just shock or something disturbing the reader won’t want to look at. It’s become popular in nature writing to acknowledge humans as a part of, instead of apart from, nature. Which is great and true. However, the reverse is often overlooked: that nature is a part of us and nature is not Easter bunnies—it is struggle and instinct, predator and prey, life and death.

KW: If you start googling around about what a good poem is made up of, one of the forefront earmarks is the use of figurative language, i.e. metaphor and simile. At their simplest essence, both metaphor and simile allow a poet to step beyond the literal and traverse into the twilight of comparison. Comparison allows for the making of the new and the creation of the joinery for the space that both poet and reader will inhabit. Yet, the simile is so often dissed, passed off as the soft step-sister to the hard-nosed metaphor. The two things are just “like” each other in the simile, while they are conflated through the metaphor. The poet Edward Hirsch says that the metaphor “creates deeper relationships with the reader.” Not only that, but that the reader “participates in meaning-making.” One characteristic these poems share is a multitude of similes. Why the decision to create similes rather than metaphor? How does working with similes help you in discovering the heart of a poem?

EB: I think if you’re observing nature you tend to think in metaphor, but if you’re participating in it you speak in simile. I’m constantly looking at nature and trying to see myself in it, to see where I fit. For example, I have a trail camera set up at a pinch point in a game trail that overlooks a draw and spring. It’s fascinating to see the difference in how predators and prey move through this area. Deer move cautiously down the trail but bobcats and bears always pause at the highpoint, for minutes sometimes, to look for opportunity. You don’t want to bump your quarry! I immediately see myself in that. It’s what I do when I come to a good view. I’m a predator; I’m like a bear.

In the Sandra Beasley piece, “Kilroy Was Here: Poetry and Metaphor as Signature,” you reference, she speaks about makership of a poem and how the use of simile is particularly appropriate when the perspective is “conscious observation,” as “Readers need to experience the thought process of the observer,” which I think is the heart of most of my writing and poetry.

I like working with similes because they are grounding and work so effectively with dualities. It’s hard for me to find use for abstracts or symbolism when immersed in the literal, but I find great power in connecting different specific things.

KW: You have, for goodness sake, 1,762 followers on your Instagram and 2114 posts (not that anybody’s counting . . .). Those posts are made up of a lot of beautiful images of what you forage, grow, find, make. (Plus, there’s a very prominent tabby.) Obviously, you are doing a lot more than just hunting out there in the mountains. The cover of your book is so striking, too: that black and white image of a woman almost contorted over a prickly pear. Lo and behold, it’s your sister’s image, so art must be in your family. I looked hard, but didn’t find a lot about your wonderful visual artistic eye, except for a podcast you did with backcountry hunters. I definitely believe that art begets art begets art, no matter what types of art intertwine. Can you talk to us about your photography and art and if/how you see it intersecting with your writing?

EB: I have always been surrounded by artists. My mother is an artist, my uncle is a professional artist, my mother-in-law did the pen and ink illustrations for my first book, and my sister-in-law is a fantastic artist as well. And as you mention, my sister, Erica Block, is a talented artist and created the linocut that is the cover of How You Walk Alone in the Dark. She made it before I put together my poetry book, but I was so struck when she showed me a photo I asked for a print, which I framed and have hanging on my living room wall. When it came time to pick a cover image it was my husband, Jay Zimmerman, who suggested Erica’s linocut. The stark black and white, tension of balance, sense of insularity yet expansion the work holds felt like a perfect fit.

Many of my poems start with a photo, which functions as a placeholder until I get my head around things and start to write. I’m lazy at keeping a journal, but I love taking photos. And they can hold a place in time that can get you back into a moment quickly. I think being surrounded by so many visual artists has made me very aware of composition and not just snapping a photo but trying to understand angles and lighting and what aesthetically speaks to the eye. Poems and photographs work in tandem for me. In both, you’re often trying to capture a moment and make it bigger than itself.

KW: Cut-throat fishing, peanut-toe squirreling (people will have to check out your Instagram), feral apple growing, facial-camouflaging, writing, librarian-ing, book-award-winning, editing, free-lancing, rabbit-choking—sorry, can’t help myself (: —what’s coming up new for you?

EB: I have boxes of feral apples in my kitchen as we speak, waiting for me to save seeds. So round two of that project! And hunting season is here and this is my first-year hunting with a recurve bow, which has been a real challenge for me to build the upper arm strength to manage. For library work I’ve read a lot of technical SQL books over the past year, so I’m excited to get back to more poetry and nonfiction this winter. On the writing front, I’m always trying to write just one more good poem. And then another. I don’t write to a project; I write to my experience at the time.