Interview with Alysse McCanna

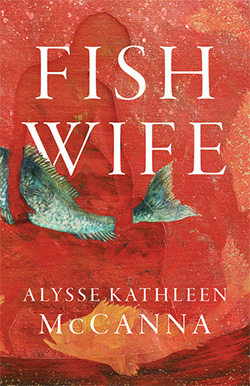

Research Rabbit-Holes, Linchpins, Lexicography, and The [ ] Wife: Poet Alysse McCanna, on her new book, FishWife by Black Lawrence Press

Alysse Kathleen McCanna is the author of FishWife (Black Lawrence Press). Her poetry has appeared in North American Review, The Rumpus, Poet Lore, TriQuarterly, and other journals. Alysse’s chapbook Pentimento won the 2017 Gold Line Press Poetry Chapbook Competition. She holds a PhD in English from Oklahoma State University, an MFA from Bennington College, and serves as Associate Editor of Pilgrimage Magazine. Alysse is an Associate Professor of English at Colorado Mountain College in the Vail Valley.

KW: Following your epigraph, a quote by Emily Dickinson on the “fictitious shores,” are two definitions for Wife and Fishwife. These definitions become the extended metaphors that set the structure of your book. I see your book, written in this way, as part of almost a particular mode of contemporary poetry. Wife and, deeply, beautifully, Fishwife inform narrative, image, word choice, metaphor, the prose of the etymological . . .throughout all the poems of this book. You seem so proficient in the language of ship and sea and deepening it into metaphor: can you tell us, one, whether you learned this language in your research of the fishwife or if you chose fishwife because of your prior experience and knowledge with the sea? And, two, why might a poet contemplating a new book consider taking this approach of the extended metaphor in writing this book? What’s the process? The gifts? The difficulties?

AKM: Like most poets, I have a long list of obsessions, and bodies of water are up there. But sea-related language and knowledge are new territory for me as a result of the creation of FishWife, even though the metaphor of life as a sea voyage in Dickinson’s poem is one I’ve been chasing for a while. I was tasked with memorizing a poem in high school and chose Dickinson’s “I many times thought peace had come.” I’m sure I chose it because it’s short and it rhymes, but it has since become a touchstone. The final line: “how many the fictitious shores/before the harbor lie.” How delightful, and yet sobering–a reminder that the world is spinning and whatever shore you think you’ve landed on, good or bad, is temporary. This poem played in my head as FishWife came into being, especially as I sifted through stores of memory for metaphor and explored new lexicons of ship and sea.

Similarly, outside of my personal experience and observation of relationships around me, most things “wife” were new, too. The speakers in the book are sometimes relaying moments from my life and at other times exploring historical or cultural marital practices. The process was both playful and intense, tumbling down research rabbit-holes and spending time with dictionaries and encyclopedias, paying attention to the minutiae of words, teasing out origins, and questioning the role of lexicography in perpetuating harm through certain usages of language. I hope the speakers as a chorus engage in the larger project of dismantling patriarchy and the bonds of traditional heteronormative relationships.

As someone who thrives in the structure metaphor can afford, as much as it sometimes frustrates me, I would of course recommend this approach to other writers! It was only after crafting a strictly biographical full-length manuscript that I realized I wanted my first book to be not only personal but also nuanced and engaging with a world outside of the self. Approaching the writing of the manuscript as partly a research process allowed me to step away when the painfully private got too hot, when I needed a new perspective or context, or desired to get lost in unfamiliar language.

KW: Despite the “rough & rude woman . . .prone to shouting” in the title of your book, your book is so…tidy. It’s the antithesis of the fishwife caricature. You, at least in this book, are a quickfire formalist, a major structure-addict. After a “quick perusal,” I found and I’m only naming a bit of what I found: haibun, prose poem, ghazal, syllabic verse, couplets (you love couplets without the rhyme), list poem, litany, tercet, crown sonnet, and fragmentation. I thought we were all contemporary post-modernist/poststructuralism/deconstructionist poets eschewing the hierarchical yoke of meter-making/form-wrangling/ pre mid-Yeats classic traditional verse . . . well, you got the idea. So what does structure do for you in poetry writing that the free-verser might want to know?

AKM: I love this characterization–I am absolutely a structure-addict! If the speakers and characters in the book are messy, complex beings, the architecture in which they exist and express themselves is strict. I think that’s how I make sense of our incomprehensible world. My obsessions with form and structure, alongside although antithesis to chaos and ruin, thus manifest in the book. I feel at most messy as a writer in the longer poems, “Wife” and “Crown for Forgetting,” but even those are in some kind of structure, whether invented, as in “Wife,” or traditional, like the sonnet crown

Perhaps this says something about my psychoses, but I can also trace some of those obsession origins–in my MFA program one of my advisors, who never minced words, didn’t like my sonnets. Looking back, they were truly terrible, but it lit a fire in me to someday write a good sonnet. That defiance and oppositional force of wanting to prove her wrong became a creative drive that ultimately turned extreme: to prove her wrong seven times. The form breaks halfway through the crown, but the first four sonnets are fairly strict syllabically and in their rhyming, although not strict in meter.

In my PhD program I took a workshop with the brilliant poet Janine Joseph that transformed my relationship with form. I fell in love with the pantoum in particular–so obsessive, reflective, circular, gorgeous. The necessity of writing a poem in form once a week for a deadline forced me to just do it, and I found myself delighted with the way filling in a structure or following a rule made my brain twist and turn to meet the challenge. I write plenty of poems in free verse, of course, but if I’m feeling stuck I find that form is always helpful in getting me unstuck.

I love seeing how contemporary poets are eschewing, embracing, reinventing, and breaking traditional forms. Form is like an unfamiliar dish–try it and you might love it, try it and you might hate it, but at least you tried it.

KW: By the time I followed your journey in this book to Part III and its opening poem, “Heat,” and its penultimate lines: “ . . .and feel alive on an ocean, surprised that I’m awake and the man beside me brings ice and wildflowers, so much true and undeserved sweetness . . .,” I almost wept. Though I assert in my first question that the terms Wife and Fishwife determine the structure of your book, I am lying or I am wrong. You sweep us through the wreckage of an early violent marriage, the sea lovers between, including the one who “sprouted copper armhair,” and the “almost husband,” and “a girl’s soft parted lips,” and the “wish wife in salmon petticoat.” I feel like Part III takes us elsewhere, a place where, finally, you can “lick the spoon.” What is the journey of your book?

AKM: I love that you were moved by “Heat”–that poem is such a catharsis to me, marking the end of one journey and the beginning of another. There are several journeys in the book, defined by, yes, wife and fishwife, the speaker’s relationships and entanglements, but also by movement and landscape. The speaker moves from the instability of the sea to the fleeing wheels of a car to a home rooted in grass and flower. While “Crown for Forgetting” is a poem of movement, the rest of the poems in Part III are grounded in place, in earth. “The Houses” may be my favorite poem of the book, where “wife” is no longer the defining characteristic of the speaker, where she is no longer bound by whatever strings define relationships, and she can experience a life that feels indulgent in its abundance of love in other shapes and forms.

Equal to the sea and its myriad metaphors, perhaps, is the role of witchery and the tarot figures, as I think of them: The Magician, The High Priest, The Lovers are familiar, and The Soldier, The Keeper, The Sailor, etc., are of my own making. Some are based on me, others are true figures in my life, others amalgamations of true figures, and some part or pure invention. They’re linchpins of narrative and journey, and puzzling out where they fit best informed the book’s chronology and flow.

KW: Black Lawrence Press and this book, Associate Professor of Colorado Mountain College in Vail, Associate Editor of Pilgrimage Magazine, 2020 Academy of American Poets Prize, winner of Six Folds 1st place voted poems, Verse Daily: what’s next?

AKM: I adore teaching, but it takes up almost all of my time–in an effort to recenter writing in my life, I’ll be spending a delicious 10 weeks at the Wurlitzer Foundation in Taos next summer, working on the next manuscript. While it’s unlike FishWife in many ways, it is also a journey and will follow a prescribed structure: that of descent into the underworld. It’s an elegiac project honoring the lives of my two young cousins who died 10 years ago. I imagine it as an epic poem, a fictionalization of their lives & deaths, engaging in the traditions of elegy and inspired by the afterlife journey manifest in so many religions and cultures–in our oldest stories. What a gift to receive such time for writing–I’m excited to see what happens next.