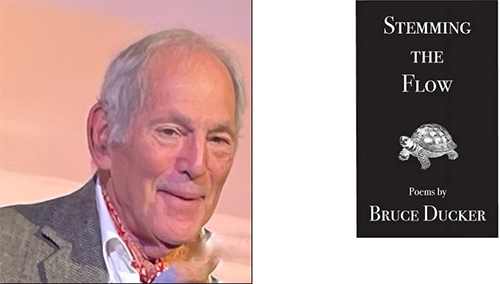

Bruce Ducker, Writing On A Matchbook: When An Award-Winning Novelist Writes A Book of Poetry

Writing On A Matchbook: When An Award-Winning Novelist Writes A Book of Poetry

Bruce Ducker’s newest book is Stemming the Flow, published by Kingston University Press. Ducker is the prize-winning author of eight novels and a book of short fiction. He has over 100 poems and stories in the nation's leading literary journals, including The New Republic, the Yale, Southern, Sewanee, Literary, and Hudson Review, and Poetry Magazine. A jazz pianist, he's also written the book, music, and lyrics for three musical comedies. Born in New York City, he lives in Colorado

KW: You’re a lawyer; you’ve written eight novels and one book of short fiction; you’ve won the Colorado Book Award for fiction and the Macallan story prize. And now you’ve just published your first book of poetry. Even though the publication acknowledgments for poems in this book are longer than my arm, I’m still going to ask my facetious question: “Are lawyers who are novelists allowed to be poets?” Seriously, if I ask my Google, “What qualifies as a novel?” All I get are descriptors like “longest genre of narrative prose fiction,” or “story about a person or group of people,” or “include[s] exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution” or a word count for the length of a novel. Huh? Where are those poetry descriptors like using rhyme or images or rhythm or writing preternaturally about “personal bellybuttons?” How do you see your novel-writing working for your poetry? Or your poetry working for your novels? What are the techniques you use from writing novels for your poems and what do you do completely different in your poems from your novels?

BD: Fiction is created by the urge to narrate, to pass on, to inform. Its language is by necessity –hard to have a novel without a plot— denotative: who, what, where, and why. (That of course does not mean a novel can’t be poetic— we have too many examples from Sterne to Daniel Mason.) The language of poetry is –too strong—I feel should beconnotative.

Robert Frost, quoted in Stemming, defines poetry as, “It almost seems as if...” Equally cryptic, the essayist Walter Pater says, “All art aspires to the condition of music. “ Let’s start there: what does Pater have in mind?

Music affects us immediately. If you use an MRI to trace which parts of the brain react to music and which to fiction, you’ll find two different patterns. Reading a book of prose, whether fiction or fact, employs the logical, substantive chambers in the right frontal cortex. Music ignites the amygdala, the seat of emotions. Although unaware of the physiology, Pater was saying that music doesn’t need vocabulary, syntax, rhythm, all the trappings of writing in language that intervene between stimulus and reaction. So I think a valid and simple definition of poetry is this: writing that stimulates emotion. The poet’s job is to make his work as close to immediate as possible. It don’t mean a thing, Duke warns, if it ain’t got that swing.

All that claptrap you got in the eighth grade –slant rhymes and true, anapests and dactyls, trimeter and hexameter, Petrarchian sonnets and Elizabethan ones-- are descriptors that come after the fact, tools to help the poet move her audience. And herself.

Many people seem afraid of poetry. They feel it requires education or special training or is too effete or too intellectual for them to bother. Men especially. I have friends who seem embarrassed by my having written a book of poems, as if I’d been caught in a love nest with a dead goat. It may have something to do with the exposure of emotion.

How does novel-writing work for writing poetry? Among other lessons, it teaches that you must sit down and write to have any hope at all. Those fleeting ideas are hummingbirds that buzz past your brain, pausing for a moment’s sip and then disappearing so quickly you’re not sure they were there. You’d best be sitting at your desk when it happens. Too, you learn the thrift of words, the weight of words, the qualities of sound when a sentence is constructed with care.

And what of the opposite: poetry writing affecting one’s fiction? I don’t really know—my words above sound so pedantic, I hesitate to add to them. For one thing, one blessed thing, a poem is over more quickly. You know whether you’re on to something or not. Usually in the midst of a novel, with every pause I wonder if I should take up quilting instead. I’ve done poems on the back of matchbooks. Some have suggested I might better have used the matches on them. You can be in the middle of a novel and have no idea whether it’s working.

Novel writing and indeed the practice of law teach the great lesson of how to work. No lawyer I know has ever told his client that he could not finish a merger agreement because of Lawyers’ Block. There again, the difference between denotative and connotative language applies. In the law, one is not congratulated for an evocative phrase, a covenant which raises fear or pity. Clarity comes first. Not a bad lesson for a poet. Novels need clarity, poems not so much. Is it a coincidence that the death of Dickens –our most declarative novelist—was followed the next year by the birth of the exquisitely poetic Proust?

All your readers are or want to be poets. Warn them that there’s a great deal of nonsense written, now filmed, about the artistic experience. I don’t know whether to blame the neurotic goths –Poe and Baudelaire spring to mind—or Hollywood. William Blake said that, for inspiration, he waited for the face of his dead brother to appear at the window. If my brother’s face appeared at my window I’d call the police. Much of the writing of poetry is simply hard work. The novelist Don Delillo maintains that he is not a writer, he’s a maker of sentences, the way others are makers of doughnuts.

Finally, what do I do differently when writing poetry versus fiction? For one thing, I worry far more about the fiction. When I’ve thrown out novels, it’s an amputation. But when I discard a poem that hasn’t worked, can’t be coaxed to the surface –is it a spoiled egg that doesn’t float?-- it’s easier, almost pleasant, like flossing your teeth. Although Talmudurges that we should be ever conscious of our leavings, even when we trim our fingernails.

KW: Wow! You are one fun and versatile writer! Here’s another one: Poets are always grumbling about the difficulties of putting together a book of poems. They labor over their poem on kitchen tables and dining floors, post multi-colored post-its on their walls, throw poems to the wind, all in trying to find the secret web that interconnects these brief and beautiful moments they’ve written about over the years. Your book Stemming The Flow is divided very simply into four distinct sections centered on particular times in your life, “Beginnings,” “Places in the World,” “Love and Marriage,” “Death and Dying,” and the surprise last section, “Making Art.” In a sense, oh Novelist, you’ve written a narrative in poetry book form about your life! Why did you choose that organization for your book? Are these poems written closely together over a short period of time or did you write these poems at various times in your life? What process did you go through in choosing these poems for this book and then deciding on which poems belonged together?

BD: The poems in Stemming the Flow were written over some forty years. My first published poem was taken by the bulwark magazine Poetry (also first to publish Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot). When the letter came, offering $6 a line, my late wife and I agreed to celebrate with a bottle of Champagne. I didn’t realize that I’d be charged for typesetting. She had a whisky, I had a beer, and we left the balance as a meager tip. I picked the poems in the book because I thought they had some merit, or if not, might bring a smile or a sigh. They fell easily into a pattern that emerged as biography. The editors at the Kingston University Press and my partner Mary McGrath were of great help organizing the copy. I’m quite pleased with the outcome.

KW: Awards, many novels, many published poems, a new and lovely collection of poetry: what’s next?

BD: What’s next? I am putting last touches on a musical comedy, On to Tobago, that had several amateur performances in Denver. And there’s that unfinished novel lingering like an uninvited cousin, needy, impoverished, deficient.

Visit Bruce Ducker’s page on the Colorado Poets Center site to read a few of his poems