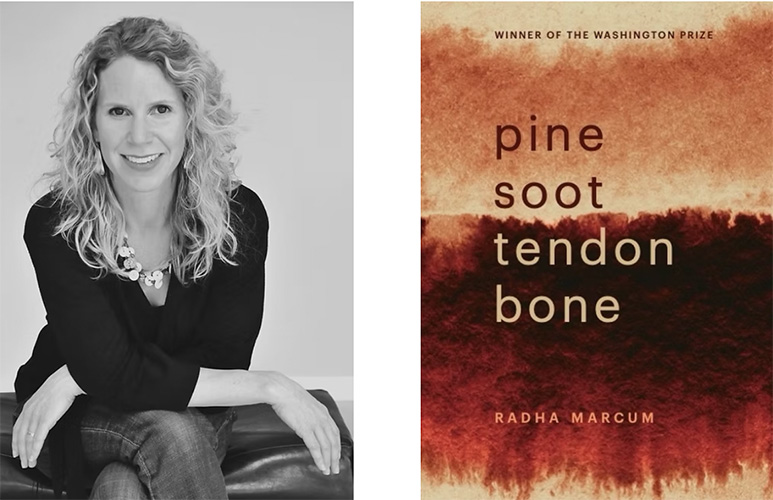

Radha Marcum

Transcending into the “with-ness”: Radha Marcum on Poetry and her new book, Pine Soot Tendon Bone (The Word Works, Winner of the 2023 Washington Prize).

Radha Marcum is a poet, writer, editor, and teacher with a focus on the intersection of the environment, culture, and personal history. She is the recipient of the 2023 Washington Prize for her collection, Pine Soot Tendon Bone (The Word Works, 2024). Marcum's first poetry collection, Bloodline (3: A Taos Press, 2017), which delves into her grandfather's involvement in building the first atomic bombs in New Mexico during World War II, won the New Mexico Book Award in Poetry in 2018.

KW: I so often hear writers and artists talk about how difficult it is to come up with a title for their work— so often that title coming as an afterthought. Yet, way back on page 69 in the notes for your book, we discover that your title alludes to Sumi-e, a Japanese painting technique rooted in ancient Chinese painting and Zen. The title Pine Soot Tendon Bone is arresting enough because it conjures the most primal elements in this world, setting up the happy expectation that we will enter a world of the book flesh to flesh, bone to bone. However, dig deeper into the spirit of the Sumi-e tradition and Sumi-e feels like the vivifying force for the whole book: form, style, content, persona/speaker. Am I right? What advice could you offer the poet looking for a new way of creating a collection of poetry beyond simply bundling poems together and hoping for the best?

RM: The unifying principles of Sumi-e didn’t come to me at the start—they were revealed at the very end as I was finalizing the text and title with my editor, the wonderful poet Andrea Carter-Brown. When my manuscript was accepted for publication, neither she nor I felt satisfied with its working title, The Velocity of Sorrow—a phrase that felt too abstract and intellectualized. After cycling through nearly two dozen alternatives, we arrived at Pine Soot Tendon Bone.

The title comes from a poem about a watercolor painted by Japanese-American artist Kakunen Tsuruoka while interned during WWII, a work I discovered in the Denver Art Museum’s archives during the early months of the pandemic. If traditionally made, the inkstone Tsuruoka used would have contained pine resin, soot, and glue from tendon and bone—materials that, like poetry itself, emerge from nature and the body yet are combined and transformed.

Tsuruoka is best known for his iconic wood-block prints of California. Having grown up in California myself, and carrying the weight of my grandfather’s involvement in developing the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, I feel implicated in that part of history. In pandemic lockdown, I felt again how the hidden and oversimplified stories—the intentional blind spots cultivated by culture—press hard on my psyche.

Yet there was something hopeful in connecting with art created during that unjust confinement. I appreciated Tsuruoka’s insistence on creating in captivity. I began using the watercolor to encourage my poetry students to attend to their immediate surroundings: the way a tree branch twists, the precise slant of a hill. If we could keep our senses alert to our unique, unfolding circumstances, maybe we could emerge from isolation with more presence of mind than we had before lockdown.

Most of Pine Soot Tendon Bone emerged from that same impulse—to write from the landscape at hand, to notice what unfolded within a few miles of my home in Boulder. But while I was engaged in this practice, the unexpected kept arising: a mass shooting in our community, the devastation of the Marshall Fire, the loss of our friend Gordon to gun violence. I did not go looking for these events, but I also didn’t push them away. They became part of the record, folded into the landscape of the book.

Although not conscious of it at the time, my approach mirrored some of Tsuruoka’s—seeking to convey both presence and absence, movement and stillness, form and suggestion. Look closely at Tsuruoka’s painting and you sense the artist’s physical presence in the mesquite tree. The gestures are kinetic. They carry tonal-emotional meaning. I prioritized that distilled, evocative quality in my poems, rather than exhaustive exploration. I chose to write plainly, with restraint, giving the reader space to enter the poems as they would a physical place.

When we were trying to decide on the book’s title, I found an abstract ink painting by Georgia O'Keeffe buried in online archives. It has a red oval suggesting both a human form and the sun filtered through layers of smoke and ash. It immediately resonated with the themes of the collection—fire, impermanence, solitude, and landscapes—and the title Pine Soot Tendon Bone. I later discovered that one of O’Keeffe’s primary teachers, Arthur Wesley Dow, taught principles of Sumi-e—unexpectedly linking her work to Tsuruoka’s.

As for advice to the poet, Consider: How might traditional principles guide you in writing poems that go beyond tradition? For example Sumi-e, like haiku, insists on direct experience. Haiku master Matsuo Bashō advised: “Go to the pine if you want to learn about the pine, or to the bamboo if you want to learn about the bamboo. And in doing so, you must leave your subjective preoccupation with yourself. Otherwise you impose yourself on the object and you do not learn.” That’s still great advice.

Be as present as possible to your life. Pay attention to the questions, concerns, and loves that resist resolution. Let them shape your writing. Read widely, engage deeply, and write from direct experience. Poetry thrives in the space between what is said and what is not. The more you engage with the unsaid, the more your work will resonate.

Remember that a collection is more than a set of poems arranged to feel complete; it is a living terrain, shaped by both intuition and intention. Some poets allow the subconscious to guide their work, while others take a structured approach, treating a book as a cohesive project. I teach a middle path: follow your obsessions, let curiosity lead, but remain aware of your poetics—the unique choices in form, voice, pattern—that shape your current work.

When I teach manuscript development, I encourage poets to pay attention to the undercurrents running through their work. What images or themes emerge repeatedly? What larger arc or rhythm can unify the collection? Allowing a book’s internal logic to reveal itself can be more powerful than forcing a narrative or structure onto it.

A book of poems should have momentum beyond chronology or subject matter. That momentum might come from a central question or conflict, a structural constraint, a set of guiding poetics—or all of the above. You won’t fully see the arc of the book until you’ve traveled far enough through it, but trust the process. Surround yourself with writers equally dedicated to the work. Hone your instincts, seek wisdom from trusted readers and mentors.

Seek inspiration beyond your primary discipline. Become obsessed. Although I don’t practice much visual art right now, I was trained in watercolor, ink drawing, and printmaking from an early age. Through that, I learned to hone perceptions while developing technique, how to direct and balance my focus on external and internal stimuli, understanding how those coalesce in gestures on the page.

KW: One feature of your book that kept jumping out at me was its juxtaposition between what I think of as the human sphere of mind and culture and the beautiful tapestry of the sensory and tactile things we co-habit with. For instance, the first “Hidden Narrative” poem is in response to a watercolor by Tsuroka. We follow the brushstrokes of the artist’s “wolf-hair brush” that leads us through a simple landscape of “big-cloud brush” and “dark shrubs like spilled tea,” until, in a parenthetical, the speaker describes the tip of the brush as “precise as the t/at the end of internment.” At that point, the landscape turns deep image: “sets the skeletal mesquite twisting,” evoking the artist’s plausible inner emotional life. Yet, I think the usual knee-jerk reaction from those unacquainted with modern nature poetry is the instant connection to the Romantics and the exaltation of nature and its sublimity. That’s not this book. Instead, there is always your recognition of the darkest shades of the human world, its often damning modernity and “skull’s dark” complexity. Why can’t or shouldn’t the contemporary poet like you just write about nature’s “music long, like woven sounds of streams and breezes?”

RM: I don’t think we can—or should—romanticize nature without also engaging with the complex realities of our interconnectedness and how humans are rapidly reshaping ecosystems. To be conscious of those intricacies is the first step toward a more conscientious relationship with our environment.

I’m deeply concerned with how we orient our attention—to landscapes, to histories, to our own experiences. The Romantic poets saw nature as a sanctuary for healing from the wounds of industrialized urban life. They were writing against the backdrop of the industrialization of the physical world. Today, poets write against the industrialization of consciousness itself, against technologies narrowing and extracting value from our attention, distancing us from even our immediate environments. Poetry, by contrast, is an ancient technology for reorienting awareness, for transmitting the lived experience of one being to another across time and space.

In Pine Soot Tendon Bone, the natural world is not a passive backdrop—it’s alive, responsive, and deeply entangled with human experience. For example, in “Fire Season in the West" human anxiety mixes with how birds, plants, trees, and grasses are responding to wildfire. I’m drawn to the ways patterns in nature both resist and adapt to change—for example, the persistence of migratory birds amid the housing developments replacing native-grass prairies and wetlands in Colorado. The book constantly negotiates this tension.

When I read ecologically oriented poets—for example, Forrest Gander, who is influenced by the Tamil Sangam poets who, two millennia ago, “believed that boundaries between inner and outer landscapes are porous and the the ultimate goal of poetry is the dissolution of any split between self and world”—I feel myself pulled into the contours of his attention, momentarily freed from the habitual patterns of my own troublesome mind. This kind attention matters because, as poets like C.D. Wright remind us, the aesthetic is moral—they are not separate.

Eco-poetry resists the fragmentation encouraged by internet culture. Instead, it offers a widening scope. It insists that we encounter circumstances directly, taking in as much as we can with empathy. Listening to friends who lost homes in the Marshall Fire, I thought of Carolyn Forche´'s concept of witness. Witness is close to what I want from poetry, but it implies a subtle separation between observer and event. Eco-poetry like Gander’s and Hillman’s model poetics that transcend that subtle separation, pushing me toward a kind of with-ness, insisting I show up not just a spectator but with implicated and embedded presence—complex, open, connected.

Poetry is ecological—not simply because it takes nature as its subject but because it insists on interconnection. Brenda Hillman speaks of bio-poésie, a poetics that does not separate the self and extract meaning from nature, but moves within it, shaped by its rhythms and substances. When I hike in the ponderosas here, I breathe out carbon compounds that the trees recycle. In turn, I breathe in their chemical signals—the myriad compounds that Japanese researchers have shown to strengthen immunity and calm my chronically over-stimulated nervous system. We are in intricate exchange.

A good poem is an intricate exchange, too—a spell calling me back to the “daily astonishments of being human at all,” as Jorie Graham says.To write with this astonishment, with attention to both beauty and destruction, awe and tragedy, is not an aesthetic exercise alone. It is an ethical one.

KW: Your first book, Bloodline, won the New Mexico–Arizona Book Award in 2018. Now you have a second award-winning book. Among other awards, you received a 2023 Folio Award for excellence in journalism. You teach at Lighthouse Writers. What’s next for you?

RM: I’m working on a series of poems about the mutated flora of radioactive landscapes inspired by the citizen scientist Mary Stamos. She collected specimens near Three Mile Island after the nuclear disaster there. Some of these new poems were published recently in Conjunctions.

In addition to teaching for Lighthouse, I run a small online community—Poet to Poet—for poets who are looking for guidance in finishing collections and navigating the literary publishing landscape. I founded it in 2021 to demystify that process, which isn’t addressed in most MFA programs.

I want poets to know that getting a book published isn’t all about talent or luck but relies on strategic steps that will increase your chances of success. I had to learn everything I know about building and publishing collections through trial and error. With Poet to Poet (poettopoet.com), my goal is to make that process more transparent. I’m thrilled that what I share in that community has been working for poets of all aesthetic types. It seems like every time I open my email, I’ve got another message from a student or mentee who has won an award or gotten their work picked up for publication.

Contact:

Follow:

- poettopoet.substack.com

- Insta: @coloradha

- FB: @radha-marcum