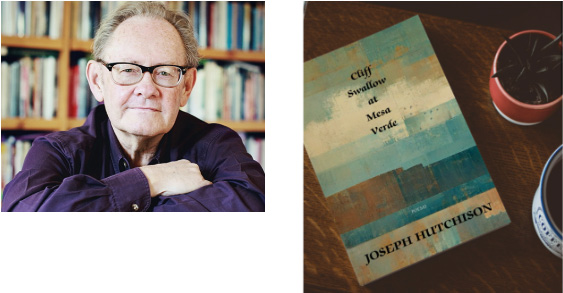

Joe Hutchison

On Guitars, Chess, Mythical Kings, and the Fresh Speaking of Good Poems: A Conversation with Joseph Hutchison on his new Chapbook, Cliff Swallow at Mesa Verde, (Middle Creek Publishing & Audio)

Joe Hutchison was the Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019. He has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management.

KW: I started teaching a workshop on writing the chapbook as a way to engage with the writing of poems as something sustained, something that gathers force as the poet begins to find the patterns and rhythms and deep meanings that can come when not writing poems as single “one-off” entities. But writing a good chapbook is not necessarily any easier than writing a full-length manuscript. The poet Lauren Davis, in an interview with Writing Workshops, asserts that “Chapbooks, because of their length, often demand more focus, so the sequence can profoundly alter the manuscript's message and overall effect on the reader.” The late Jake York, a beloved Colorado poet, has a wonderful article at the Kenyon Review on how the chapbook can be developed “to communicate a certain enthusiasm about the literary work in ways that might teach readers how to participate in this enthusiasm.” I preface with all this to say that I found your chapbook beautifully contemplative as it quietly pulls us through the quiet angst of a man in a fraughtful age. Can you talk to us about, first, why you chose to write the chapbook instead of a full manuscript, and,andand second, how you found or determined the structure of your chapbook? For instance, I’ll argue that your very first poem, Snow Whiplashing in the Wind, teaches the reader how to read this chapbook:

Stormwind of history, stormwind of metaphor—

visions the mind calls to this moment

blind you to it instead—blind

and drag you off

into your humanity, in chains . . .

JH: I have to confess that I didn’t conceive of a chapbook before the poems come into existence. I am essentially a wandering writer, a writer without a map. Each poem comes in its own way, and it’s not until I look back that I see how certain poems have worn a path in the long grass. When you say the whiplash poem teaches how to read the collection, I think, “Well, maybe so.” But I’m unsure. Probably because, when I sit down to write, I don’t know where I’m headed, I’m not convinced that the path is really a path when I look back. I’d hate for a reader to take this poem as a map is what I mean. It’s more like a guitar chord, and each poem that follows strikes a different but somehow related chord. If anything at all gets taught, it’s how to listen for ways in which the chords are connected. I hope Cliff Swallow inspires that kind of listening in its readers.

KW: I’m wondering about the extensive use of reference and allusion in this chapbook. So many of your poems begin with epigraphs cited to other poets: Gluck, Trakl, Merwin, Ginsburg. And the very first poem in this chapbook sets up the journey of the seeking spirit here so beautifully with a simple list of books and a “storm wind of metaphor” that we will see sustained in the other poems. Oregon State has a pretty thorough discussion on the use of allusion, making this statement:

Allusions draw connections between text and reader

by harnessing them into the space where context resides.

Allusions are the tendrils of a text that expand its field

of association, but that also serve to intensify the intellectual

and aesthetic possibilities of a given moment.

I’m still thinking about the depth of these poems and how quietly and swiftly you create that sense of depth. Can you talk a bit about the rewards and possible complications of using allusions and references (i.e. what if your reader doesn’t recognize them?).

JH: This is a tantalizing issue. My intention is for allusions and references to operate, most of the time, as nice-to-haves, enhancements or filigrees that the main work of the poem doesn’t depend on. Of course, sometimes the main work depends on a certain kind of knowledge. Take “To a Voice,” for example—probably the most allusive poem in the book. Let’s say a reader doesn’t know that “i.m.” is an abbreviation for “in memoriam,” and that “in memoriam” refers to a text written in memory of a dead person, in this case W. S. Merwin. Such a reader might get a “vibe” from the poem, but little more. The poem does set a high bar for the reader, and I suppose the poetic question is, is that fair? But what a poet owes the reader isn’t fairness, or message-simplicity, but a form or structure that aligns with the poem’s intentions, as distinct from the poet’sintentions.

When I write, I almost never start out with a message I want to convey. I start out with a feeling, an intuition, very vague, which usually arrives with a few words and a certain cadence attached. I write to discover the meaning of all that. The more complex the meaning, the more the poem (for me) will become allusive. People who love poetry, it seems to me, tend to have a high tolerance for this kind of complexity. Maybe it’s the game aspect of poetry. With some poems the reader plays checkers, and with others the reader plays chess. And there are some poets—like Emily Dickinson, Wallace Stevens, Paul Celan, Sylvia Plath—with whom the reader plays three-dimensional chess!

Of course, it helps to remember that every word embodies allusions. The first sentence of my response to your question had the word “tantalizing” in it. The word means “tormenting or teasing with the sight or promise of something unobtainable," maybe a reason so many people stop reading poetry after reading it in school! The word derives from Tantalos, a mythical king of Phrygia in Asia Minor, who after dying was punished (different offenses are cited in different traditions) by being made to stand in a river up to his chin, under fruit-laden branches, and whenever he tried to eat or drink, the water or the branches would withdraw. Too many people have this kind of reaction when they read certain poems that would better be dealt by simply saying to themselves, “This one’s not for me.”

Let me add that “this one’s not for me” should be said with “for now” in the background. The more poems we read, the more we recognize connections among them. This is why poems that baffle us at age 20 suddenly open for us at age 30 or 40. I was 40 before, in rereading Frost’s poem “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening,” it hit me that the phrase “between the woods and frozen lake” is probably an allusion to Dante’s Inferno, which begins with Dante lost in a dark wood and ends with him face-to-face with Satan, who is embedded in a frozen lake. Readers can decide for themselves whether this affects the meaning of Frost’s poem. The main point is that reading poems, if the poems are good, is not a matter of “one and done.” Good poems tend to speak to us freshly throughout our lives.

KW: You were our Colorado Poet Laureate from 2014 to 2019 and currently direct the Professional Creative Writing program for University College, University of Denver. You’ve been around, as they say, my friend. Can you talk about the changes you’ve seen in the Colorado literary scene over the past decade and why poetry still matters today?

JH: I came up in Denver, and the Denver scene was what I knew best. As I started to publish books, I made contact withcontacted more poets, at the beginning—I’m talking mid-1970s to mid-1980s—my experience of Colorado poetry was almost entirely along the Front Range. I had far more contact with poets outside the state than in the state, again because of my publishing activities. Back when we had the Colorado Council for the Arts and Humanities, It really wasn’t until the Laureate gig came along that I had a mission and the necessary support to travel to other parts of the state, and I have to say I was blown away by the richness on display everywhere I went. Communities that support poetry arise organically, but seldom without the support of folks from local universities and colleges. Whatever the local situation, reading and writing poetry are passion projects. The fact that we continue having students who want to write poetry, in a nation where there is so little reward to doing so, is a testament to the need for it. Historically, there has never been a human society that did not have poetry. If we had some kind of apocalyptic technological meltdown, we could survive without computers, even without electricity. But we wouldn’t thrive without poetry.

KW: New chapbook, constant stream of publications, most notably now online, editor of the Bristlecone: Poetry of the Mountain West, your “Perpetual Bird” blog . . . and your intention to move down from the mountains: what’s next for you?

JH: We haven’t moved down yet! And it’s sobering. We’ve lived for thirty-plus years in an unincorporated section of Jefferson County called Indian Hills, and every clear morning I’ve been able to start the day with a contemplative view of Mount Blue Sky. (Hey: maybe one of this interview’s readers will want to move up to the mountains!) That aside, there is a Colorado Poets Laureate anthology in the works—the first of its kind in our state—that’s been curated by us five living poets laureate: Andrea Gibson, Bobby LeFebre, David Mason, Mary Crow, and moi. My personal hope is that it will inspire more anthologies that will represent the full diversity and excellence of the poets at work in Colorado. I’ve also sketched out a book rethinking some of our assumptions about what poetry is and how it works. And, of course, I hope there are many more poems in my future, as a writer and a reader. Two kinds of joy. What more could I ask?