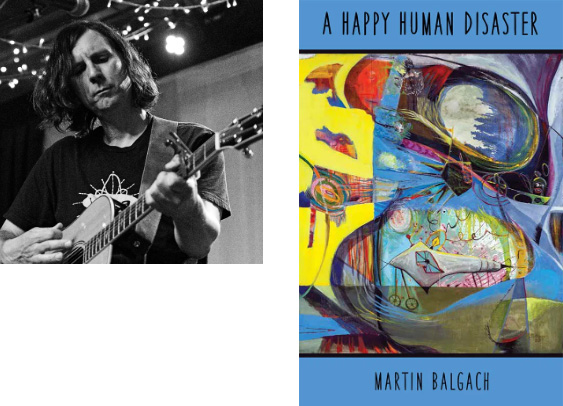

Martin Balgach

The Beautiful Profusion of Self: An Interview with Indie Artist Martin Balgach on his new book, A Happy Human Disaster (Main Street Rag Enterprises LLC)

Martin Balgach is a singer-songwriter and author based near Boulder, Colorado. He is the author of two books, A Happy Human Disaster and Too Much Breath. His work has been published in journals such as The Bitter Oleander and Verse Daily. He recently released two singles, September and All These Places.

KW: Congratulations on your second book, Martin. I’m going to jump right in here and ask you about the dazzling “stuff” of your book. It opens with the poem, “A Short History of Me,” but through, I would say at the very least, the liberal use of simile and the broadening of the speaker’s persona from “I” into “you” and “we,” the book moves into a vast and dazzling universe of places, things, and perspectives. The book made me think about a 2014 AWP essay, Not Releasing the Genie: On the Poetry of Stuff vs. The Poetry of Knowledge, written by the poet David Wojahn when “googling” was becoming a “thing.”Wojahn talks about the ”skitteriness” of the poem that gathers info from Google that can find “six million, six hundred and ninety thousand results” when you plug in “How to sex chickens.” Yet Wojahn also remarks how the “profundities” of “good poems” also “arise from their very skitteriness.” There’s a lot of stuff in your poems, detailed, precise, colorful, meaningful stuff. How did you find the balance between stuff and profundity?

I want to know what I’m made of—

I wish it were honey and stone,

details, not circumstance.

I sing these steel wool blues with the energy of Christmas.

I become a dull tomahawk

catching moonlight

on a still-silver blade.

from Steel Wool Blues

MB: Kathy, thanks so much for making the time to talk to with me. I appreciate it, and you honed right in on what I’m up to, and what I grapple with! I think it’s safe to say that all my poems start with an impulse, an utterance; I’m never really trying to get anywhere and I never—well seldomly—have an agenda, which is both magical and scary. This is likely a result of an early obsession with beat writers when I was studying Philosophy as an undergrad. It framed my early sense of writing, scribbling madly in journals trying to be Kerouac or Ferlinghetti or Snyder and that freedom was a counterpoint to writing dense, rigid essays on say, Hegel or Wittgenstein. I was caught between worlds and Philosophy was wonderful but overwhelming, so poetry, and associative writing, offered me a refuge, a little freedom from my academic work—and I still carry that with me today.

I eventually learned that the poem has a responsibility to make sense, at some level. When I went back to grad school for my MFA, one teacher in particular, Richard Jackson, helped me recognize the need for coherence, and while he embraced associative writing, he trained me to make decisions between what was obfuscating and what was needed to power the poems, to keep them discernable.

So, in terms of process, I think I’m most capable of finding what I need to know when there are no restrictions or rules. I like the idea of submitting to the exploration, but I edit with an eye for coherence, while making sure to leave evidence of the flickering, of the sparks.

I suppose the psychology of association plays a role here too, as we are each, to borrow your phrases, “vast, dazzling, and skittery” and sure, some parts of us are random, but I hold onto the belief that a frequency of the poem has to function on a level I’m not aware of, it needs some mechanism of, I don't want to say subliminal, because that feels generic, but beneath the surface, behind the scenes—all the things we’ve known and perceived and all the granular bioproducts of all the experiences—they are in there somewhere and they comprise that speaker’s changing persona. It’s from that glorious mess that the poet carves out that [seemingly unhinged] very specific similes from essentially infinite possibility and it can all exist without rules, well, maybe we need some rules, but I also need the poem to be something that doesn’t have to add up the way most things in our lives add up. I think this is what poems do?

KW: You published your first book of poetry, Too Much Breath, with Main Street Rag, too, in 2010 to good reviews. Now, fifteen years later, you publish this second book. I’m always interested in stories that go against the grain of what we all imagine the poet’s life to be like: the successful poet bringing out a book every couple of years and building and building their career that way. But how often is that the true human story? What are those silences so many poets face that can span days, months, years, decades? And then break through to a new poem or chapbook or book? Tillie Olsen in “Ways of Being Silence” reminds us that “Literary history and the present are dark with silences: the years-long silences of acknowledged greats; the ceasing to publish after one work appears; the hidden silences; the never coming to book form at all.” Carl Phillips in his essay, On the Value of Silence for Writers, quotes Ellen Bryant Voigt on writer’s block:

'That’s not how I think of it,’ she responded, and went on to explain

to me how a snake, in order to attack, must first recoil to establish a

position from which to attack. As I understand the analogy, the attack

is the act of writing, and the period of recoil, of retraction, is many

things: reflection, thinking, revision of thought, remembering.

Tell us about your silence. Tell us about finding voice.

MB: This is a big question! For me, it is a question of identity and logistics. I’ve been writing poems since I was a teenager, and it never felt like a vocation or anything I would do “professionally.” Through a series of things, I found myself working in the business world and did not pursue academia.15-20 years ago, I found myself in jobs that left me searching for another aspect of my identity, and the choice to pursue the MFA while working full-time in business was a choice to redefine who I was, or to at least add a new dimension.

So, this is a long way to say I’ve never written full-time or tied it to making a living through writing, so the gaps are long. Too Much Breath came together after grad school, and I’ve been chipping away at A Happy Human Disaster for over 10 years. Maybe longer. I’ve lost track! After grad school, I did some editing for the great journal, Many Mountains Moving, I published poems online and in print, was writing criticism that appeared in important journals like Rain Taxi, and then my wife and I had our son, and priorities changed. I felt like I was on the edge of becoming a serious poet but it did slip away, or I let it slip away. I haven’t published or written a poem in years. But I also hike and ski a ton, my family and I have a camper and my son has been to so many national parks and incredible places. I play music, write songs, and I also work full-time for my career—in front of a glowing screen banging a keyboard, so, yes, it is sad to not be actively writing and publishing right now, but how many people can we be? I also have to market this book!

KW: You are a songwriter and a performer, as well as a poet. I’ve been wondering what the difference is between the songs you write and the poems you write. I would think there would be a difference just because you are presenting those pieces in very different environments: to a live, cheering audience in a gig space and to a possibly bleary-eyed and solitary reader at the midnight kitchen table dripping coffee on your book! In The Difference Between Poetry and Song Lyrics published in the Boston Review, the poet Matthew Zapruder posits that “The ways the conditions of that environment affect the construction of the words (refrain, repetition, the ways information that can be communicated musically must be communicated in other ways in a poem, etc.) is where we can begin to locate the main differences between poetry and lyrics.” Is your writing process different when you write a song? a poem? How do you know when a piece is meant to be sung alive on the stage or sung silently in the heart? And why aren’t all poets song writers?

MB: I agree with Zapruder! Song lyrics surely have poetic qualities, but it’s a different function than literature. Beyond the process of letting oneself follow the creative impulse, I don’t see too much in common between my poems and my songs. The differences are vast.

Many (most!) of the choices in a lyric are pre-determined by all the other things that have to interconnect and function as a whole. I have no doubt that having read a ton of poetry and written and rewritten and thrown away so many poems has undoubtedly made me a stronger lyricist, but I also know many great lyricists who aren’t avid poetry readers.

One of the biggest differences is length—a song is going to be about 3 minutes, maybe 4. There is only so much that can be said, and it’s probably a bit more akin to formal verse than free, as rhyme scheme, cadence, meter—all those elements—have to work within the music, and as a singer, there are words you just can’t easily sing, or that just don’t work with a chord or note, and there are words that are ideal to sing but they might impact meaning. And you generally need a chorus, and usually a bridge. Poems, at least free verse, might have a refrain, a turn, a hook, a resolution, but the structure is not intrinsically tied to and defined by instrumentation. That’s the critical difference.

All of it, poems, songs, lyrics, spoken word, are amazing and essential and matter more than many so things, but I think the distinction is clear, for me anyhow. Hey, if someone thinks lyrics are poetry, that’s cool. I’m not going to argue with them. But in my orbit, they serve two completely different functions—despite their commonalities.

KW: A new book, two recently released singles, All These Places and September, published essays and book reviews . . . what’s next!!?

MB : Yes! I’ve been busy! Little mid-life angst is good fuel. I’m looking forward to promoting the book and doing some readings in Colorado, and I welcome any inquiries or invitations. I’m all in on music right now—I have another single titled, Not the Same, releasing later this summer, and that will be followed by Burn Away (For a Comet) soon after. I’ve been writing a ton of songs, playing out live, which has been a blast, and for now it feels like where I need to be. I’m on the bill for the Lafayette Music Festival in October, which will be a big stage for me. I’m hoping the book will gain some exposure on the merch table at shows. If folks are interested, my website is martinbalgach.com, and my Instagram is @martinbalgach. The songs are on all the streaming services. I just hope to share poems and songs and do all these things that are vital to my sense of self. And as Pessoa said, “Each of us is several, is many, is a profusion of selves.” And yes, I hope some self in here writes more poems!