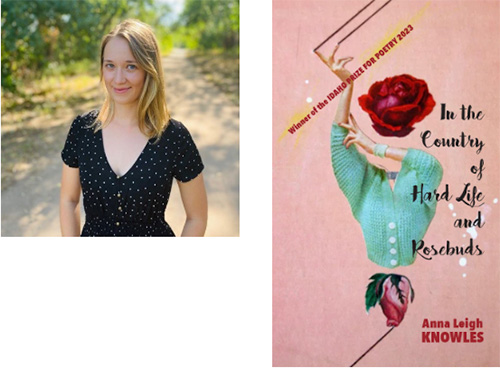

Anna Leigh Knowles

What Language and Love Can Do: Anna Knowles’ In The Country of Hard Life and Rosebuds as a Novel-in Verse (Winner of the Idaho Poetry Prize and Finalist for the 2025 Colorado Book Award)

Anna Leigh Knowles is the author of the poetry collections In The Country of Hard Life and Rosebuds (Idaho Poetry Prize 2023 and Finalist for the Colorado Book Award 2025) and Conditions of The Wounded (Wisconsin Poetry Series, 2021).The recipient of several awards and scholarships, Knowles received her MFA from Southern Illinois University-Carbondale and a BA from University of Colorado-Denver. She currently teaches in Denver.

KW: Congratulations on your book being a finalist for the Colorado Book Award in Poetry this year. What a wonderful achievement. I interviewed Alysse McCanna for CPC on her book, FishWife, which won this year. Certainly, the judges must have had quite a tough time choosing between the three finalists. Poet Roy Bentley, one of the judges for the Idaho Prize 2023, which this book won, praises your book, saying that “it reads like a novella.” I found that interesting, especially since there’s been an uptick in interest in the novella. The Poetry Foundation offers an informative learning prompt by the poet and children’s writer Meg Edan Kuyatt on what she calls the novel-in-verse. Novella, novel-in-verse—ultimately, there is this wonderful resurgence of a poetry/narrative hybrid. Yes, you have a collection of poems, but as Bently says, the collection reads as a narrative. Character and voice change progressively in this collection. Kuyatt reminds us that the best novels-in-verse excel in creating “emotion, intimacy, and focus.” I certainly see those three qualities here. Are we catching the hem of something or totally off!?

AK: I think I was halfway through writing the early drafts when I realized I was writing a very story-driven book, albeit a story woven by family myth, imagination, history and a version of Kentucky that no longer exists, if it ever did at all. I wrote the final version of the book when I was living overseas, so I was very concerned with rootedness and connectivity of place, what keeps us tethered to the idea of home. Two poetry collections I had in mind when thinking about placing these poems into a larger narrative story were Rita Dove’s Thomas and Beulah and Nickole Brown’s Fanny Says. Both books encompass storylines that tie narrative threads in subtle ways that often make me forget I’m even reading poetry. They also both tell beautiful stories of family. I wanted to do both and trusted where the drafts and my relationship to the content were telling me. Ultimately, I hoped the whole book would read as a novel-in-verse and a huge love poem to a specific people and place.

KW: One of the standout elements in your book is voice. I’m from Ohio and we used to look across the river at Kentucky. I remember place through your voice, though there is something “old from the hills” in your voice that I wouldn’t expect in the work of a young poet:

Don’t recall the direction of wind

or time of year, but it was when the day trains came

through Fallsburg so little more than a gap-tooth

of light was involved for sure. Call it June.

A familiar man drunk as a lord under the sun’s

thumbed udder. A tenant farmer . . .

What?! “the sun’s thumbed udder”? “Gap-tooth of light”? And yet by the end of the book, this voice changes as though the speaker of these poems changes, or speakers change, transform:

I grip the bed rails shaped

like a lotto ticket, the garden

her mattress became—stained

gardenias bloom large.

Writer’s Digest has a little article called “Finding Your Poetic Voice." By the time I read through that, it seemed like finding voice in poetry is so darn hard: this mixture of grammar and syntax, form, and the music of prosody, subject matter, and finally, magic. Yet, the voice in your poems seems effortless. Of course, there is natural talent in writing poetry, but I think that there is also long study and experimentation. Can you talk about your journey into the voices of this book?

AK: I’m obsessed on a lyric level with what language can do, so I’m always very intentional about lyricism, although it was probably the more difficult aspect of writing the book. The voices came naturally, as many of them were character-based in that I had very specific language in my head from family stories and a specific geography of place in writing about family. It’s interesting that you noticed the speaker’s transformation–which surprised me–as I agree that the speaker goes through a sort of metamorphosis from beginning to end, and comes to a certain understanding about the self and her placement in the larger web of family history as the book progresses. The question the book asks is about belonging.

KW: I remember hearing the poet Donald Justice, who was known for his experimentation in form, say one in a workshop something like “if a poem didn’t look good on the page, it probably isn’t a poem yet.” All of your poems look very beautiful on the page. You often write in couplets and tercets, use lots of white space, create interesting stanzas forms etc. I don’t think of you as a formalist poet, though maybe a new formalist, yet I agree with the poet John James that you “deploy a stunning variety of lyric forms.” I remember all the times I tried to get students to understand that the poem wants to be more than a blob on the page, to try and find its form, whatever that might be. I found an interesting blog on Read Poetry that compares free verse with organic verse, suggesting that organic poetry creates its own structure, while free verse is somehow different than that, somehow “free-er”. Can you talk about the tidiness and elegance of your poems? And if you work better when that structure is predetermined by you or if that structure comes later, after you have written out a few drafts of the poem.

AK: I struggle with form a lot. When in doubt, I usually veer toward the couplet or tercet by proxy because they are more comforting to write in when the poem is still expanding and growing. After a few revisions, if I feel the form is still messy or clunky, I’ll pull everything back into a larger prose block and break the enjambments where they feel natural or enhance an image or idea. From there, I try to organize in the most coherent way possible and let the poem breathe in areas where I tend to push language into more claustrophobic structures.

KW: Two poetry books, multiple awards, MFA, current teacher in Denver, and, I think, a little one at home . . . what’s next?

AK: I’ve been working on some new work that excites me and allows me to explore my own identity more intensely than my other books. I’ve been trying to write a short poem for years, so hopefully I can figure out how to do that without feeling like something is being sacrificed. I’m reading all the poetry I can and am playing around with a larger novel draft when the baby sleeps.